Whether gasoline, diesel, or electric, automakers work hard to wring every last drop of mileage out of their vehicles. Much of this effort goes towards optimising aerodynamics. The reduction of drag is a major focus for engineers working on the latest high-efficiency models, and has spawned a multitude of innovative designs over the years. We’ll take a look at why reducing drag is so important, and at some of the unique vehicles that have been spawned from these streamlining efforts.

Boo To Air Resistance

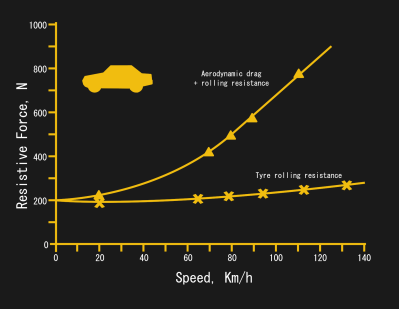

Whether you’re looking for lower fuel economy or just trying to get as many miles as possible out of your battery, drag is the enemy. Pushing a car through the air takes work, and the faster you go, the more the air pushes back. Rather unfortunately, drag is proportional to the square of velocity, so as speed doubles, the drag force quadruples. Above roughly 20km/h (12.4 mph) or so, aerodynamic drag is the biggest force working against the car, eclipsing rolling resistance as speeds increase.

Measures can be taken to reduce this drag, of course. Creating a car with a smoother profile helps, one that delicately splits the air at the front and lets it gently recombine at the back. Reducing the size and number of protuberances helps, as does reducing the overall frontal area of the car. With careful attention to these factors, it’s possible for automakers to reduce drag considerably, with attendant benefits to efficiency.

The slipperiness of a car is often talked about in terms of the coefficient of drag, or Cd. This is a dimensionless coefficient that quantifies the amount of drag a given object generates as it passes through a fluid, such as water or air. In some analyses, it’s also important to consider CdA – the drag coefficient multiplied by the frontal area of the vehicle. Two vehicles can be equally streamlined in design, but if one is bigger than the other, it will naturally experience more drag.

As a guide, a flat plate trying to force its way through the air would post a Cd of 1.28, while a bullet at subsonic velocity might come in at 0.295. Typical modern sedans and coupes have drag coefficients around 0.25 to 0.3, with SUVs often posting higher numbers of around 0.35-0.45 due to their higher, boxier designs. Sportscars built with a focus on downforce naturally feature higher Cd numbers due to induced drag from aerodynamic elements.

The 1999 Honda Insight, an early hybrid car, came in at the bottom of this range, claiming a Cd of 0.25, a number considered class-leading at the time. Newer competitors in the space have further improved on this, however. The Mercedez Benz S 350 BlueTec came in at 0.24, as did the Tesla Model S at its launch in 2012. Since then, the new Porsche Taycan has a Cd of just 0.22, with the new-for-2021 Tesla Model S claiming a figure of just 0.208. The latest Mercedes EQS pips both, however, with a figure of just 0.2.

It’s Not Just How You Look

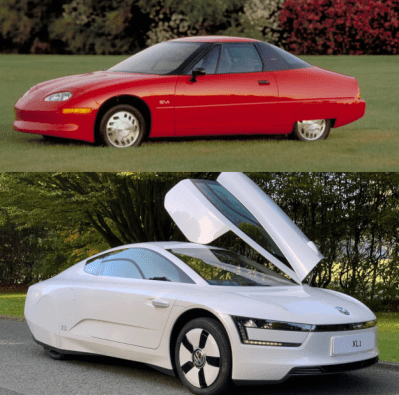

It’s interesting to note that while early hybrids from the 1990s adopted obviously swooping, streamlined designs, modern cars have eclipsed these numbers without going for such formless egg shapes. Often, aerodynamic gains can be found by carefully shaping the flow in subtle ways, rather than focusing on the macro shape of the car as a whole. Other gains can be had by virtue of technological progress; electric cars have eliminated large radiators up front and thus feature much more streamlined bumpers, for example.

Production cars are naturally limited in their design choices, however, which forces automakers to compromise where streamlining is concerned. Some optimisations are easy, such as swapping out whip antennas for low-profile sharkfins, or adding aerodynamic covers to wheels. Others are more difficult — regulations state that side mirrors are mandatory in most jurisdictions, while many automakers push for cameras to be adopted to shave off the protrusions to minimise drag. Even seemingly minor rules, such as headlight-to-ground distance or hood height regulations, can have a major effect on a design. Customer expectations around interior comfort and luggage space can be a problem, too. Thus, some of the lowest drag numbers posted have been from experimental, concept vehicles.

The General Motors EV1 of 1996 stands out for a stunningly low Cd of just 0.19. It was GM’s attempt to build a real, usable electric car for the masses. The vehicle attracted a die-hard fanbase amongst participants in the limited lease program, but was hamstrung by its limited range and two-seater interior. The cars were recalled at the end of their leases and the vast majority were crushed. Similarly, the Volkswagen XL1 matched the EV1’s Cd of 0.19 upon release in 2013. Designed to a tight brief from chairman Frederick Piech to wring 100 km out of one liter of diesel. Fitted with a 35kW two-cylinder engine and a 20kW electric motor, the production version managed 0.9L/100km in real world testing. Limited to a production run of just 200 units, the vehicle featured no side or rear vision mirrors, and no rear windscreen. Passengers sit in tandem, one behind the other, rather than side by side, to minimise the frontal area for maximum efficiency. Taking things even further, vehicles such as those entered in the World Solar Challenge are designed for optimal performance to make the most of their limited solar power. The Sunraycer entry from 1987 featured a streamlined body posting a Cd of just 0.125, necessitating the driver to lay almost supine in the car. Similarly, entries in the Shell Eco-marathon follow much the same philosophy, with 2018’s Eco-runner 8 coming in at a slippery 0.045.

The 1930’s Were a Great Time for that Swooped Look

However, the history of streamlining cars far predates the post-1973 fuel crisis that saw Americans start buying compact cars in droves. The basic aerodynamic concepts behind making objects slip through the air were being applied long ago, with the streamlining craze of the 1930s touching everything from trains to cars to toasters. The Tatra T77A was one of the first cars designed with a focus on aerodynamics, but more advanced designs also came to fruition.

Perhaps the most extreme design of this early era was a car known as the the Schlörwagen, named for its designer, Karl Schlör. The prototype, built on a rear-engined Mercedes chassis, reportedly posted a Cd of 0.15. It achieved this with design choices considered wild at the time; the entire car was shaped in a single, smooth egg shape with minimal protrusions, scoring it the nickname the “Göttingen egg”. It entirely enclosed not just the rear wheels, but also the front, necessitating a 2.10 m wide body that was considered ridiculously oversized for the time. Windows mounted as flush as possible to lessen any disturbance to the air, giving the car a futuristic look far ahead of its time. However, the car was never seriously considered for production, despite its impressive design.

Overall, it’s likely we’ll see future models from major automakers continue the downward trend in drag numbers as the battle for mileage heats up in the electric car space. Plenty of gains are still left on the table as regulators move slowly on rules surrounding mirrors and other technologies that could improve numbers further. With that said, consumers will continue to demand minimum standards of comfort, space, and safety that mean we’re unlikely to be driving around in pointy teardrops anytime soon.

0 Commentaires