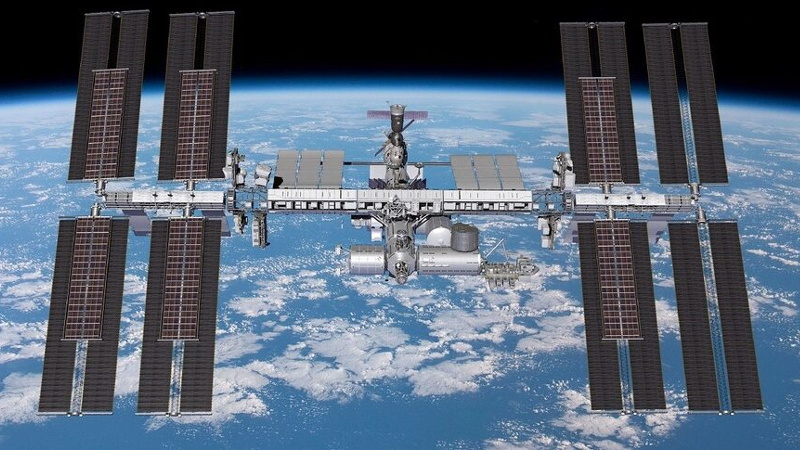

Astronauts are currently installing the first of six new solar arrays on the International Space Station (ISS), in a bid to bolster the reduced power generation capability of the original panels which have now been in space for over twenty years. But without the Space Shuttle to haul them into orbit, developing direct replacements for the Stations iconic 34 meter (112 foot) solar “wings” simply wasn’t an option. So NASA has turned to next-generation solar arrays that roll out like a tape measure and are light and compact enough for the SpaceX Dragon to carry them into orbit.

Considering how integral the Space Shuttle was to its assembly, it’s hardly a surprise that no major modules have been added to the ISS since the fleet of winged spacecraft was retired in 2011. The few small elements that have been installed, such as the new International Docking Adapters and the Nanoracks “Bishop” airlock, have had to fit into the rear unpressurized compartment of the Dragon capsule. While a considerable limitation, NASA had planned for this eventuality, with principle construction of the ISS always intended to conclude upon the retirement of the Shuttle.

But the International Space Station was never supposed to last as long as it has, and some components are starting to show their age. The original solar panels are now more than five years beyond their fifteen year service life, and while they’re still producing sufficient power to keep the Station running in its current configuration, their operational efficiency has dropped considerably with age. So in January NASA announced an ambitious timeline for performing upgrades the space agency believes are necessary to keep up with the ever-increasing energy demands of the orbiting laboratory.

Made in the Shade

Replacing the Station’s original “Solar Array Wings”, or SAWs, with new ones isn’t really an option. For one thing, they’re far too large. Even in their retracted position, each SAW is more than 4.5 m (15 ft) long, considerably larger than what can be fit into the Dragon’s trunk. SpaceX likely could have come up with some Dragon variant capable of carrying expanded payloads, as they’ve already been contracted to do as part of the Artemis lunar program, but the time and cost involved would have been prohibitive.

But more importantly, removing the SAWs would be a massive undertaking that would undoubtedly be plagued with unexpected problems. The first step would be retracting them, but as pulling just one of the arrays in turned out to be a six hour nightmare when ground controllers last attempted it in 2006, the chances of getting all eight of them collapsed into a more manageable configuration would seem pretty poor. Plus the procedure would need to be done without disrupting normal operations aboard the Station, and afterwards, the old panels would need to be safely disposed of in some way.

Instead, NASA decided to take the easy way out: rather than actually replacing the old panels, they would simply install smaller panels directly on top of them. By not altering the original SAWs, the installation procedure would be far safer for the Station, and it would also allow the new panels to take advantage of the existing sun-tracking mounts. Naturally this means a sizable portion of the original SAWs would be in permanent shade, but given the higher efficiency of the new panels, it still ends up being a net positive in terms of energy production.

But that only solves half of the problem. These new solar arrays would still need to be compressed into a form small and light enough to fit into the back of the Dragon.

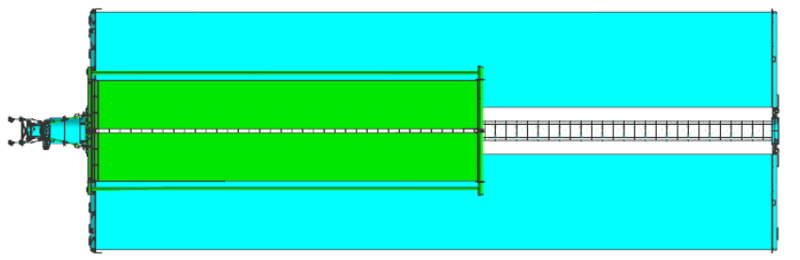

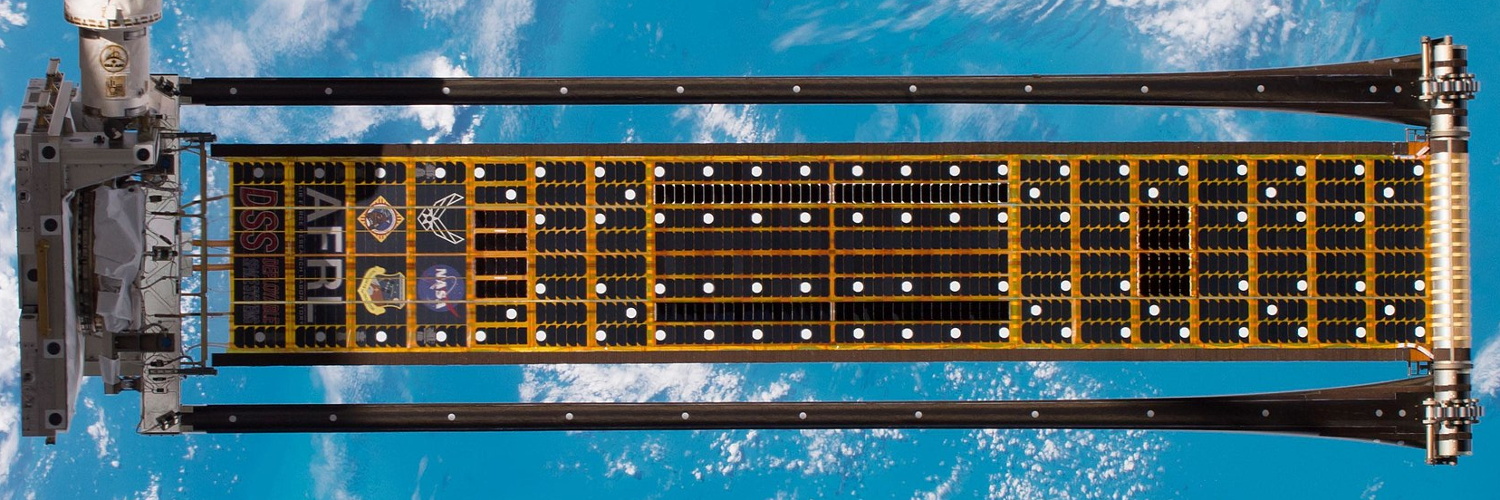

Rolling Out ROSA

The solution, developed through a collaboration between the Air Force Research Laboratory and Deployable Space Systems, is the Roll Out Solar Array (ROSA). Without the rigid strictures and hinges used in traditional deployable solar arrays, the ROSA can be stowed as a tight cylinder and unrolled once moved into its final position. The integrated booms on either side of the solar panels are made of a composite material, and are able to unfurl the array using nothing more than the potential energy stored when they were coiled up on the ground. This capability makes them highly reliable, and holds particular promise for future applications where human intervention may not be possible.

The first two ROSAs arrived at the Station earlier this month as part of the SpaceX CRS-22 mission, with the other four expected to be delivered before the end of the year. Installation of each ROSA requires two spacewalks, one to install a modification kit to the existing SAW structure, and the other to mount and unfurl the panel. NASA says that when deployed, each of the 18 m (60 ft) ROSAs will produce approximately 20 kilowatts; roughly equivalent to what each degraded SAW is currently delivering.

Technically there’s no reason ROSAs couldn’t be installed over all eight of the original SAWs, but at least for the time being, NASA believes the additional 120 kilowatts the ISS will receive with six upgraded arrays will be enough to meet current and future power demands. It’s also likely that, in classic NASA fashion, they want to keep one pair of SAWs in their original configuration on the off chance that there is a problem with the modified arrays.

But the International Space Station is just the beginning. Assuming they work as expected in low Earth orbit, NASA plans on installing similar roll out arrays on the Gateway lunar outpost. This small space station will serve as a rallying point for astronauts travelling to and from the Moon’s surface, as well as a proving ground for the next-generation technology that could eventually take humans to Mars and beyond.

0 Commentaires