Just a few weeks before Atlantis embarked on the final flight of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, a small Mexican company by the name of Squad quietly released Kerbal Space Program (KSP) onto an unsuspecting world. Until that point the company had only developed websites and multi-media installations. Kerbal wasn’t even an official company initiative, it started as a side project by one of their employees, Felipe Falanghe. The sandbox game allowed players to cobble together rockets from an inventory of modular components and attempt to put them into orbit around the planet Kerbin. It was immediately addictive.

There was no story to follow, or enemies to battle. The closest thing to a score counter was the altimeter that showed how far your craft was above the planet’s surface, and the only way to “win” was to put its little green occupant, the titular Kerbal, back on the ground in one piece. The game’s challenge came not from puzzles or scripted events, but from the game’s accurate (if slightly simplified) application of orbital mechanics and Newtonian dynamics. Building a rocket and getting it into orbit in KSP isn’t difficult because the developers baked some arbitrary limitations into their virtual world; the game is hard for the same reasons putting a rocket into orbit around the Earth is hard.

Over the years official updates added new components for players to build with and planets to explore, and an incredible array of community developed add-ons and modifications expanded the scope of the game even further. KSP would go on to be played by millions, and seeing a valuable opportunity to connect with future engineers, both NASA and the ESA helped develop expansions for the game that allowed players to recreate their real-world vehicles and missions.

But now after a decade of continuous development, with ports to multiple operating systems and game consoles, Squad is bringing this chapter of the KSP adventure to a close. To celebrate the game’s 10th anniversary on June 24th, they released “On Final Approach”, the game’s last official update. Attention will now be focused on the game’s ambitious sequel, which will expand the basic formula with the addition of interstellar travel and planetary colonies, currently slated for release in 2022.

Of course, this isn’t the end. Millions of “classic” KSP players will still be slinging their Kerbals into Hohmann transfer orbits for years to come, and the talented community of mod developers will undoubtedly help keep the game fresh with unofficial updates. But the end of official support is a major turning point, and it seems a perfect time to reminisce on the impact this revolutionary game has had on the engineering and space communities.

Flights of Fancy

By the numbers, there’s no question that DOOM is the game which has most frequently graced the pages of Hackaday. After all, porting the 1993 shooter to a new or unusual piece of hardware is a rite of passage for hackers. Minecraft also pops up plenty of times, though in many cases, it’s more about some new in-game feat of engineering than anything corporeal.

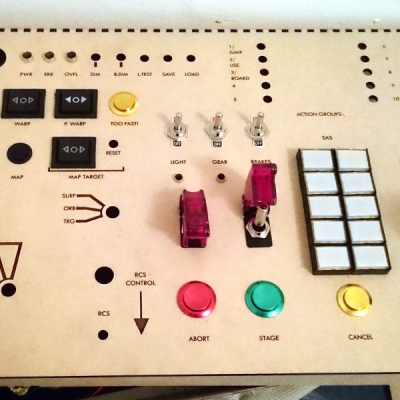

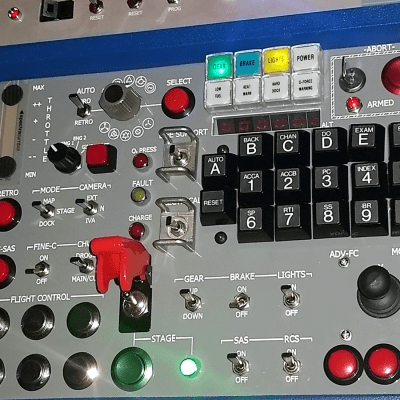

But as for which single game has inspired the most peripherals, Kerbal Space Program surely takes the top spot. The first KSP controller we covered was back in 2015, and it combined a joystick, lighted push buttons, aircraft style toggles, and a trio of screens to read out various bits of in-game data. To somebody who’s never piloted a craft in KSP it might seem like overkill, but each and every one of those buttons and displays would be playing an important role as your meticulously designed lander descended to the surface of the Mun, KSP’s stand-in for Earth’s nearest celestial neighbor.

Speaking of the Mun, the first appearance of KSP on Hackaday was when alum Brian Benchoff launched a mission to map Kerbin’s rocky natural satellite in 2012. Notably his attempt took place long before the game officially added in the sort of instrumentation that was necessary to observe a celestial body from orbit, so he used community developed add-ons to build his mapping satellite. After days of scanning the Mun from a polar orbit, he had collected enough data to recreate his own three dimensional model of the in-game world that was suitable for 3D printing.

Bringing Space Down to Earth

The array of projects we’ve seen focused on KSP is certainly impressive, but the people creating custom cockpits for their virtual spacecraft are just one tiny segment of the larger community. What the game will truly be remembered for is how it took a complex subject like orbital mechanics and brought it to millions of people in an approachable and fun way. You can read all about how the Apollo spacecraft performed the trans-lunar injection (TLI) maneuver, but if you really want to wrap your head around it, just start up KSP and do it for yourself.

KSP made space exploration relatable in a way which wasn’t possible before. Earlier spaceflight simulators such as Orbiter — as impressive as they were — were a bit too grounded in reality to capture the public’s imagination. The key to what made KSP so successful was how expertly the developers balanced realism and fun. NASA could challenge the public to recreate their own real-world missions in Kerbal’s solar system knowing that the game had all the principle parts necessary to fashion a serviceable analog, but without the pedantry that would make it impossible for the armchair astronaut to complete. KSP didn’t just reaffirm what everyone already knew, that spaceflight is monstrously complex, it served as a way to teach the average person why it’s so difficult.

Whether there’s a preteen or an retiree at the controls, there’s something new to discover by playing KSP. But more than that, the game can be used as a powerful learning tool even if the audience is just passively watching. Scott Manley started out by simply recording himself building rockets in KSP, and parlayed that into Internet fame as a science educator with more than 1.2 million subscribers on YouTube. He was recently tapped as an expert spaceflight consultant for the Netflix film Stowaway, where he used KSP to show the director what a practical Mars spacecraft might look like.

Felipe Falanghe’s plucky rocket simulator, inspired by his childhood experiments with fireworks, will be forever remembered as one of the most successful indie games of all time. But that won’t be its most lasting impression on the world. While an astronaut aboard the Space Shuttle in the 1990s might have credited Star Trek for igniting their interest in space, there’s an excellent chance that the first person to step foot on Mars will have clocked in plenty of hours in Kerbal Space Program.

0 Commentaires