If you were born in the 1960s or early 1970s, the chances are that somewhere in your childhood ambitions lay a desire to be an astronaut or cosmonaut. Once Yuri Gagarin had circled the Earth and Neil Armstrong had walked upon the Moon, millions of kids imagined that they too would one day climb into a space capsule and join that elite band of intrepid explorers. Anything seems possible when you are a five-year-old, but of course the reality remains that only the very fewest of us ever made it to space.

Did You Once Dream Of The Stars?

The picture may be a little different for the youth of a few decades later though, did kids in the ’90s dream of the stars? Probably not. So what changed as Shuttle and Mir crews were passing overhead?

The answer is that the Space Race between the USA and Soviet Union which had dominated extra-terrestrial exploration from the 1950s to the ’70s had by then cooled down, and impressive though the building of the International Space Station was, it lacked the ability to electrify the public in the way that Sputnik, Vostok, or Apollo had. It was immensely cool to people like us, but the general public were distracted by other things and their political leaders were no longer ready to approve money-no-object budgets. We’d done space, and aside from the occasional bright spot in the form of space telescopes or rovers trundling across Mars, that was it. The hit TV comedy series The Big Bang Theory even had a storyline that found comedy in one of its characters serving on a mission to the ISS and being completely ignored on his return.

A few years ago a Chinese friend at my then-hackerspace was genuinely surprised that I knew the name of Yang Liwei, the Shenzhou 5 astronaut and the first person launched by his country into space. He’s a national hero in China but not so much on the rainy edge of Europe, where the Chinese space programme for all its progress at the time about a decade after Yang’s mission had yet to make a splash beyond a few space watchers and enthusiasts in hackerspaces. But this might be beginning to change.

Everybody’s Launching Rockets, It Seems

As we approach two decades since Shenzhou 5, it seems as though the Chinese space program has rarely been away from the news. On the Moon last year the latest in their ongoing Chang’e series of probes successfully retrieved surface samples and sent them back to Earth, while looking forward they have inked a deal with the Russians to co-operate on a manned Lunar outpostin the 2030s.

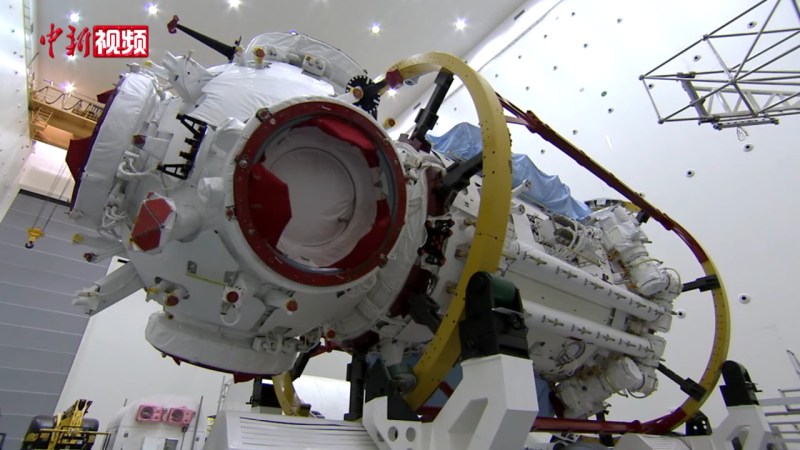

In Earth orbit the Tianhe module that will form the heart of the next in the Tiangong series of space stations received its first crew, and will be complemented by further modules over the next year. Meanwhile on Mars, their Zhurong rover landed on the red Planet aboard the Tianwen-1 mission and has been wowing us with pictures of its landing site, and there are ambitious plans for sample return missions and an eventual manned presence in the 2030s.

The sheer variety and pace of these parallel missions is immediately reminiscent of the Cold War era space race and at first sight seems far more ambitious than its Western equivalents, but of course the Chinese program is not the only one pointing its rockets skywards. The Russian space agency Roscosmos will no longer be involved with the ISS after 2025 and will bring its many decades of experience to the construction of its own orbiting outpost, while the Indian ISRO agency will continue both its successful Maangalyaan Martian orbiter and Chandrayaan Lunar programmes and is continuing with the test program leading to a planned crew in orbit aboard the Gaganyaan craft in 2022. If we thought that a two-pronged space race was exciting, one with four or even five participants should ignite the world’s interest like nothing before!

So given the likely array of craft heading skywards from China, India, and Russia, how is it looking from the side of the planet in which Hackaday’s headquarters are based? We’ve seen enough coverage of the ISS and the various contenders for ferrying crew and supplies to it, the NASA Mars rovers, and other scientific craft to know that American and European space exploration efforts are alive and kicking. But if we’re in a space race how will their near future compare to the others? For that, the special sauce comes in two forms; international co-operation in the form of the Artemis program, and the craft and parts from private sector companies that will form part of it. This has the lofty aim of returning humans to the Moon by 2024, and its first mission will launch an uncrewed test capsule aboard an SLS rocket to orbit the moon and return home, in November this year.

Maybe You Don’t Need To Be A Nation State To Race Into Space

Meanwhile there remains all the hype about the Martian plans of Elon Musk, which has at least satisfied any need we might have had to see prototype mega-rockets crash into the Texas countryside. Aside from the jostling between billionaires for the ultimate space toys though, the arrival of SpaceX, Blue Origin, and their host of competitors signals a new and previously unseen aspect to this space race that couldn’t have happened five decades ago. It’s likely that the market for smaller satellite launches will largely move to the private sector over the coming years, but at the space exploration end this increases the number of players outside the realm of nation states. American spacecraft parts have been made by private aerospace contractors for decades, but the work has been done under the auspices of NASA rather than by a company. What will be the effect of a space race between Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk for example, a dystopian corporate nightmare or a fresh and dynamic competition to those other nations? Time will tell, but one thing’s for sure: there will be a lot for space watchers to consume.

It’s said that there was disillusionment among members of the Apollo-era astronaut and cosmonaut corps during the 1970s as the enthusiasm for space exploration fizzled out and humanity’s next stop remained firmly in orbit rather than against a Martian horizon. It’s fitting then that some of them are still alive to see the start of a new space race, and that the seed will be planted in kids worldwide which will take some of them into careers that power space exploration towards the end of the century. Most of us will probably be too old to wish to be an astronaut or cosmonaut by now, but if the last space race is anything to go by we’re in for a treat as spectators with this one.

Header image: L-BBE, CC BY 3.0.

0 Commentaires