Between the 1930s and the 1950s, something sort of strange happened in the United States. The infant mortality rate went into decline, but the number of babies that died within 24 hours of birth didn’t budge at all. It sounds terrible, but back then, many babies who weren’t breathing well or showed other signs of a failure to thrive were usually left to die and recorded as stillborn.

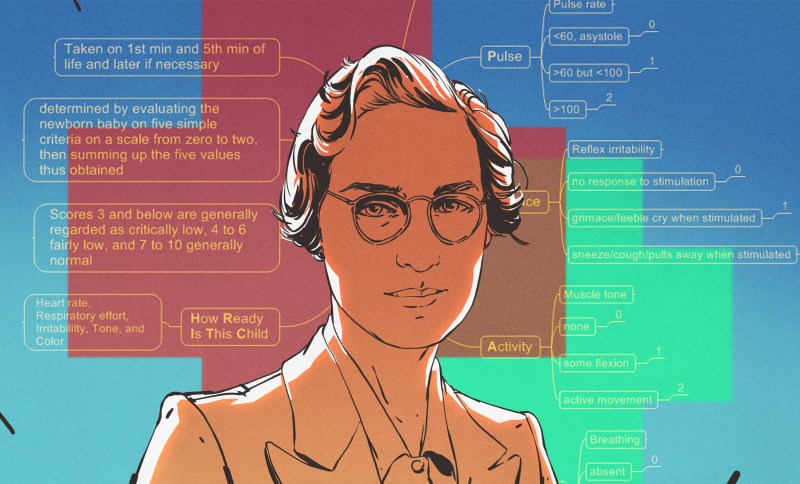

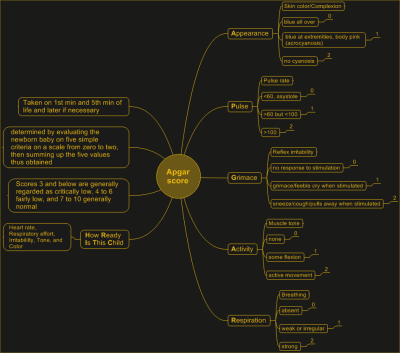

As an obstetrical anesthesiologist, physician, and medical researcher, Virginia Apgar was in a great position to observe fresh newborns and study the care given to them by doctors. She is best known for inventing the Apgar Score, which is is used to quickly rate the viability of newborn babies outside the uterus. Using the Apgar Score, a newborn is evaluated based on heart rate, reflex irritability, muscle tone, respiratory effort, and skin color and given a score between zero and two for each category. Depending on the score, the baby would be rated every five minutes to assess improvement. Virginia’s method is still used today, and has saved many babies from being declared stillborn.

Virginia wanted to be a doctor from a young age, specifically a surgeon. Despite having graduated fourth in her class from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Virginia was discouraged from becoming a surgeon by a chairman of surgery and encouraged to go to school a little bit longer and study anesthesiology instead. As unfortunate as that may be, she probably would have never have created the Apgar Score with a surgeon’s schedule.

Determined to Be a Doctor

Virginia Apgar was born June 7th, 1909 in Westfield, New Jersey, which is about twenty miles outside of New York City. She was the youngest of three children born to Helen May (Clarke) and Charles Emory Apgar.

Her father Charles was an insurance executive, amateur astronomer, amateur inventor, and ham radio enthusiast whose radio work exposed an espionage ring during WWI. Apgar had become interested in amateur radio after hearing someone boast about getting election results before the newspapers could print them. He built most of his own equipment and recorded several radio transmissions around the start of the war, some of which aroused his suspicion. Sure enough, the station they were coming from was owned by the German empire.

One of Virginia’s brothers died early on of tuberculosis, and the other suffered a chronic illness. By the time she graduated Westfield High School in 1925, she was determined to become a doctor. Virginia graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1929 having majored in zoology and minored in physiology and chemistry. Then she went to Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and graduated fourth in her class in 1933. Four years later, she had completed her surgery residency there as well.

A Medical Wonder Woman

Although Virginia may have had the credentials and the intelligence to go far as a surgeon, there’s one thing she didn’t have — male genes. Allen Whipple, the chairman of surgery at a nearby hospital discouraged her from pursuing a career as a surgeon simply because he had seen one or two women try and fail. Whipple encouraged her to go into anesthesiology — a relatively new field — instead.

He believed that to advance anesthesiology was to advance surgery itself, and he felt she could make a significant contribution. Undeterred, Virginia studied anesthesiology in residency for six months at the University of Wisconsin, and then spent another six months at Bellevue Hospital in New York City.

In 1938, Virginia returned to Columbia P&S as the director of the college’s newly-established anesthesiology division. She had the honor of being the first woman to head any division at the school, and it came with a lot of responsibilities.

Virginia spent the 1940s being an administrator, teacher, recruiter, coordinator, and practicing physician. In 1949, she became the first female full professor at Columbia P&S and stayed there until 1959.

The Apgar Score

Part of her job was providing anesthesia during deliveries, so she spent quite a bit of time around newborns. In the 1950s United States, one in 30 newborns died at birth. Virginia was determined to solve this problem, even though she wasn’t really in a position to do anything about it.

She noticed that although the infant mortality rate was decreasing, the number of deaths within 24 hours of birth stayed constant. As she was in a position to see a lot of births and document trends, she came up with a way to rate newborns’ vitality with a simple five-point matrix.

The Apgar Score is a backronym that stands for Activity, Pulse, Grimace, Appearance, and Respiration. In more revealing terms, the point is to rate the baby’s ability and willingness to move, plus its heart rate, irritability, coloring, and breathing.

Babies are supposed to cry when they’re born — it helps them transition from breathing mucus to breathing air. A non-crying baby would be given a score of 0, while a baby who gasped and sputtered would earn a 1, and a baby with good lungs would rate a 2 in that area. If necessary, all five tests would be run again in five minute increments as long as the baby showed improvement. It worked well, and soon many hospitals had implemented it as standard procedure.

Virginia worked with pediatricians, obstetricians, and other anesthesiologists to establish a physiological foundation for the success rate of using the Apgar Score. To do this, they analyzed babies’ blood chemistry to help correlate the scores with the effects of labor, delivery, and having the mother under anesthesia.

Shining Light on Birth Defects

Virginia left Columbia P&S in 1959 to get a Master of Public Health degree from Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. She worked for the March of Dimes Foundation from 1959 until her death in 1974, eventually becoming Vice President. She also directed the research program dedicated to the prevention and treatment of birth defects.

During this phase of her life, Virginia also wrote and gave lectures, traveling thousands of miles each year to promote early detection of birth defects and the need for further research. In 1965, she became a clinical professor of pediatrics at Cornell University School of Medicine and taught teratology, which is the study of birth defects.

Honorary Mother of Many

Throughout her career, Virginia published dozens of scientific articles along with several layman-level essays for various newspapers and magazines. She also co-wrote a book called Is My Baby All Right? that explains common birth defects and aims to teach expectant mothers how they can prevent them from happening.

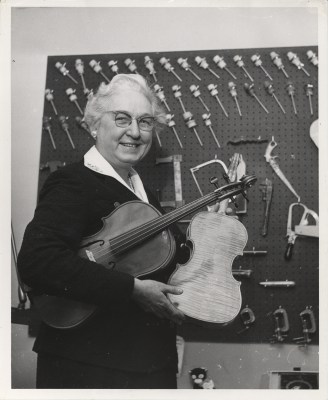

Virginia received many awards over the years, including three honorary doctorate degrees. She never married or had children, but considered music to be a big part of her life. During the 1950s, a friend introduced her to the art of making instruments, and together they made a string quartet’s worth of instruments — two violins, a viola, and a cello.

Virginia devoted her life to helping others live, and she never retired. She died of cirrhosis on August 7th, 1974.

0 Commentaires