Most people remember Charles Lindbergh for his non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic which made him an international celebrity. If you are a student of history, you might also know he was at the center of a very controversial trial surrounding the kidnapping of his child or even that he had a dance named after him. But did you know he was also the co-inventor of a very important medical device? Turns out, medicine can thank Lindbergh for the creation of the perfusion pump.

The What?

A perfusion pump is a device that allows organs to be sustained outside the body using oxygenated blood or a suitable analog. A researcher, Alexis Carrel, had the suitable analog fluid and was convinced that he could keep organs alive in vitro, but was unable to devise a pump mechanism. Lindbergh was up to the mechanical challenge and, with Carrel, invented the machine in 1935.

While they didn’t become medically important themselves, they were the precursor to things like a modern heart-lung machine that has saved countless lives. At the time, many thought Lindbergh might be more famous in the future for this invention than his transatlantic flight. But today not many people remember his medical invention.

Why Lindbergh?

If it turned out Lindbergh invented some device for pilots, that wouldn’t be very surprising. But why a perfusion pump? The story goes back to when his sister-in-law suffered heart damage from rheumatic fever. Doctors said the damage was irreversible because the heart couldn’t survive long enough without pumping to allow for the surgery necessary.

Of course, Lindbergh was well known for challenging what could and couldn’t be done and he wondered why a machine couldn’t keep the heart alive. No one seemed very interested in the idea until he mentioned it to an anesthesiologist, Palulel Flagg, who knew that Carrel was working on the very thing.

The Partners

Carrel was, by all accounts, an odd fellow. But if Charles Lindbergh wanted a meeting, you took it. The day after Lindy found out about Carrel, they met at his lab where there had been two unsuccessful attempts at constructing a pump already.

Carrel was, by all accounts, an odd fellow. But if Charles Lindbergh wanted a meeting, you took it. The day after Lindy found out about Carrel, they met at his lab where there had been two unsuccessful attempts at constructing a pump already.

Lindbergh had some ideas and working with a glass blower, produced a prototype. Carrel was impressed and offered space in his lab. However, Lindbergh’s fame was a constant problem and despite efforts to keep his work low-key, people were all anxious to meet the famous flyer.

Carrel had already won the Nobel prize for essentially inventing vascular surgery. He also pioneered the use of chlorine to wash out wounds, a great advance before antibiotics were available. He was a bit eccentric, insisting his lab assistants, for example, always wear black and, apparently, held some occult beliefs. He died awaiting trial in France for being a Nazi sympathizer after World War II.

Trial and Error

There were two key problems: circulation and avoiding bacterial infection. Lindbergh produced one prototype that wasn’t perfect, but did keep a carotid artery alive for a month. In 1931, Lindbergh published his results unsigned.

There were two key problems: circulation and avoiding bacterial infection. Lindbergh produced one prototype that wasn’t perfect, but did keep a carotid artery alive for a month. In 1931, Lindbergh published his results unsigned.

By 1935, the device was near perfection. The device was glass and could be made sterile in an autoclave. Sterile cotton filtered the incoming air. There were three chambers: the top one contained the organ in question. The lowest chamber held the perfusion fluid. Gravity pulled the fluid down until the liquid was back where it started.

However, the fluid had no where else to go and, unlike a human body, there was no kidney to clean everything up. This required frequent changes of fluid which invited contamination and threatened the sterility and stability of the system.

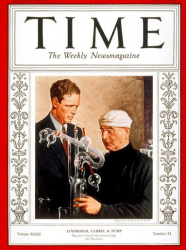

In 1935 the pair kept a cat organ alive for over 18 days. The news was so impressed that they wound up on the cover of Time magazine. We don’t know if Time was impressed with the invention or with Lindbergh’s involvement, although you can assume it was a bit of both.

However, the press became sensational and soon stories were circulating that Carrel was growing embryos and that Lindbergh was growing himself a new heart. Carrel clearly had used Lindbergh for his publicity value, but this started to backfire.

Perfusion Today

Both men fell into scandal around World War II and work on the perfusion pump stopped. By 1950, interest in keeping organs alive during surgery renewed and better methods were found. But it was Lindbergh and Carrel who paved the way for things like open heart surgery and even organ transplants with their miraculous perfusion pump.

Organ transplants have come a long way, and your next organ might come from a porker. Or maybe it will come from a 3D printer.

0 Commentaires