For some reason, I’m always interested in why things are called what they are. For example, I’ve been compelled in the past to research what Absorbine Senior is. Not that it is important, but Absorbine Junior is a smaller size of horse liniment, so you don’t have to buy a drum of ordinary Absorbine just to rub down your sore thumb. So it isn’t a mystery that I would find myself musing over why we call a flashlight a flashlight.

You don’t think of a flashlight as flashing, under normal circumstances, at least. Turns out the answer lies in the history of the device, its poor beginnings, and our willingness to treat imperfect components as though they were much better than they are. That last point, by the way, still has ramifications today, so even if you aren’t a fan of flashlight history, keep reading.

Portable Lighting

Ever since people learned to use fire, there’s been a desire for portable lighting. Torches, candles, and even oil lamps have all had their place. But burning things for light in small cramped spaces leaves a lot to be desired. It isn’t surprising that people quickly turned to electricity when that seemed to be feasible.

To make a good portable light, though, you needed a good battery and a good bulb. Both of those things were not immediately forthcoming. Early batteries, in particular, had wet chemistry. They were heavy and they needed to be kept upright.

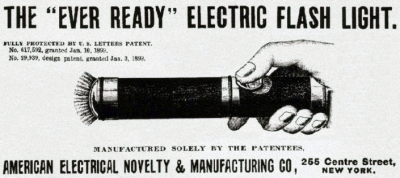

The patent assignee — the American Electrical Novelty and Manufacturing Company — donated a few of the devices to the New York City police department. They were impressed, but the bar was pretty low and we wouldn’t think much of these lights today. The company did make a success of it, though, and would eventually become known as EverReady.

The patent assignee — the American Electrical Novelty and Manufacturing Company — donated a few of the devices to the New York City police department. They were impressed, but the bar was pretty low and we wouldn’t think much of these lights today. The company did make a success of it, though, and would eventually become known as EverReady.

You’ll notice that even in the early advertisements, the word “flashlight” appears. It turns out, the low-quality battery and filament conspired to create a light that wouldn’t stay on very long. Turning the light on almost immediately caused the battery voltage to droop. The result is you’d get a little flash of light that would immediately dim until you let the battery rest for a second.

Better Everything

Of course, everything gets better over time when it comes to electronics. Tungsten filaments were a big help and battery tech got better, too. These days even an incandescent bulb isn’t found very often as solid-state equivalents are generally better. If you do find a regular bulb, it is probably filled with gas like xenon.

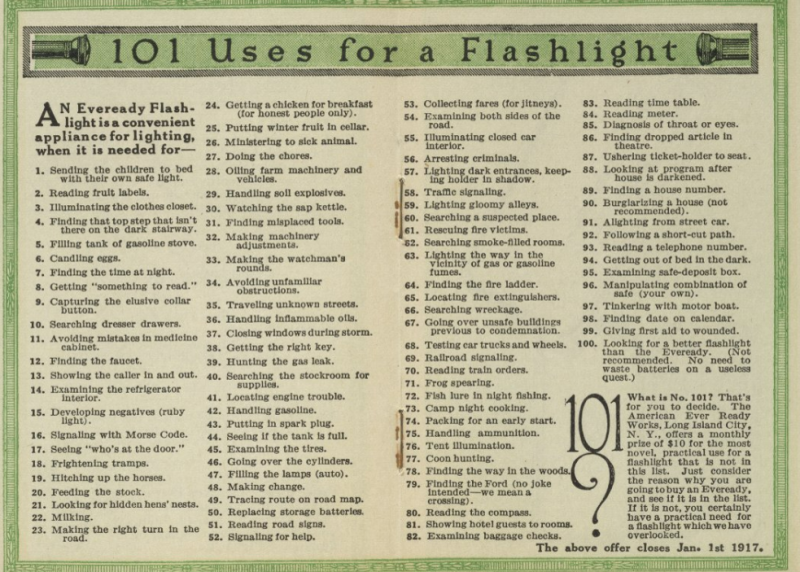

Still, a clean, cool portable light had its uses. By the early part of the 1900s, you could find 101 Uses for a Flashlight and a wide variety of different types were available, as you can see in this pamphlet.

Circuits

Even today, lightbulbs are a strange circuit component and require special handling. We like to think of them as purely resistive loads with stable characteristics and we like to think of batteries as ideal voltage sources, too. Neither of those things are, of course, true.

There are really two things, at least, that happens when you try to power an incandescent bulb. First, a real battery isn’t perfect. So while you may think that the battery looks like a perfect 1.5 V cell, it really looks more like a perfect cell in series with a small resistor. The better the battery, the smaller the resistor and the less effect it has on the circuit performance.

For example, suppose the cell has a 1/4 ohm of internal resistance. Further, imagine that you have some (for now) ideal light bulb that will draw 1.5 mA at 1.5 V meaning it should look like a 1000 ohm resistor.

If you look at a circuit like that in a simulator, you’ll see there’s not much difference since the 1/4 ohm is so small compared to the 1K. But if you play with the numbers, you’ll see as the ratio gets smaller, the effect of the voltage and current into the load makes a difference.

More Problems

The other problem with a practical flashlight is that filaments don’t act much like resistors. A filament will have a certain resistance value when cold, but that resistance will increase rapidly when heated. This change in resistance causes an inrush current when you apply power that can be many times higher than the nominal operating current.

This can be a common problem when you are trying to drive a real light bulb directly from a digital output. That initial inrush current can cause havoc with an output that is rated sufficient for nominal operations. In some designs, the varying resistance of a lightbulb is used as a design parameter.

So all these things combine to give us the flashlight. A high-resistance battery that droops as the poor-quality filament draws a high inrush current. It was fortunate, I suppose, that any light was forthcoming, at all.

Nowadays, of course, a flashlight doesn’t flash unless you want it to. There are gas-filled bulbs, LEDs, lasers — even our phones have a dedicated flashlight key. Some flashlights have a lot of LEDs. Or, you can go with fewer LEDs but more — ahem — power.

0 Commentaires