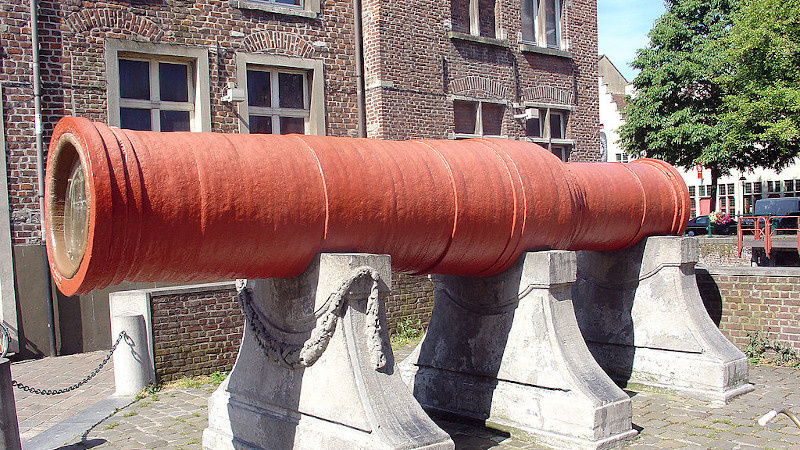

For a happy weekend away in early September, I joined a few of my continental friends for the NewLine event organised by Hackerspace Gent in Belgium. You may have seen some of the resulting write-ups here, and for me the trip is as memorable for the relaxing weekend break it gave me in a mediaeval city as it is for the content of the talks and demonstrations. We took full advantage of the warm weather to have some meals out on café terraces, and it was on the way to one of them that my interest was captured by something unexpected. There at the end of the street was a cannon, not the normal-size cannon you’ll see tastefully arranged around historical military sites the world over, but a truly massive weapon. I had stumbled upon Dulle Griet, one of very few surviving super-sized 15th century siege cannons. It even had a familiar feel to it, being a sister to the very similar Mons Meg at Edinburgh Castle in Scotland.

How Do You Contain A Small Bomb With Wrought Iron?

There is probably enough material in the wars and sieges in which these guns would have been employed to furnish a history PhD or two and at least one earnest historical documentary, but for me there was another entirely separate source of interest. This cannon was made in an age when firing a cannon was in itself a risky business, so how did the metalworkers who made it ensure that it was strong enough to contain the explosion of its charge? Probably the closest modern equivalent can be found in a 20th century naval gun, something which archive films show as being manufactured from single cast billets by forging around a former with a steam hammer. Those barrels would have used specific steels selected for their metallurgical properties, and processes and machinery simply unavailable in earlier centuries.

The answer can be seen on closer inspection, especially so with Scotland’s Mons Meg. Instead of being manufactured from a single billet these weapons are constructed from individual wrought iron staves held in place by iron hoops in much the same way as the wooden staves of a traditional barrel are assembled into a whole. This material, manufactured by an extremely labour-intensive process of repeatedly working pig iron, has the required strength and elasticity to withstand extreme forces, but for all that the barrel remains a composite of multiple separate pieces. It’s fascinating to me as someone who grew up around metalwork to see the very significant level of skill that went into producing and assembling these parts without mechanical assistance except possibly from rudimentary water hammers. The British TV show Time Team produced a very small scale replica barrel for one a few years ago, which you can see below the break. From the video you can see today’s smiths could match the production, but it’s the skill of making the high quality wrought iron that’s largely been lost.

Dulle Griet was used by the Gent city state in its campaigns, before being captured by one of their adversaries. It survives in one piece which is more than can be said for Mons Meg, which burst one of its iron rings during a ceremonial firing in 1680. There’s a question as to whether these guns (like the super-sized aircraft carriers of today) had as much symbolic value of projecting the most power for their owners alongside their military value, but one thing’s for certain: to be on the side facing their fire would not have been a pleasant experience.

Dulle Griet can be inspected by anyone with a few minutes as they walk the streets of Gent, while to see Mons Meg requires tourist entry to Edinburgh Castle.

Header image: Karelj, Public domain.

0 Commentaires