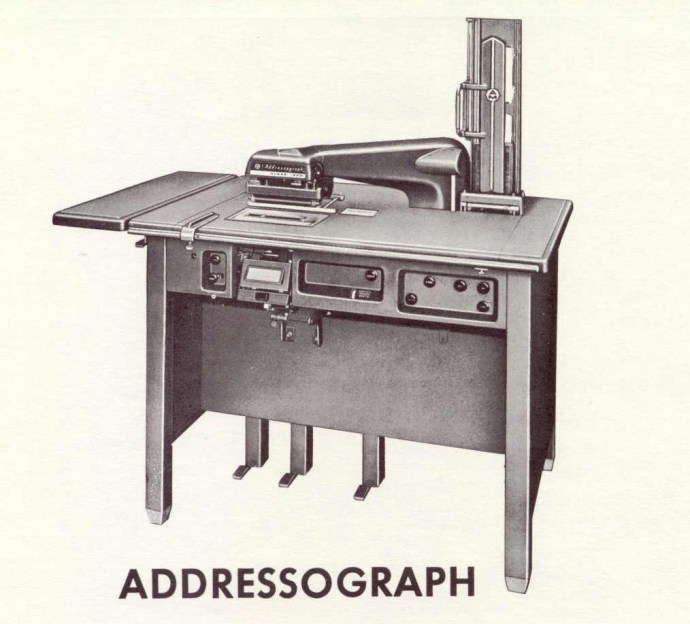

If you can’t imagine writing a letter on a typewriter and putting it in a mailbox, then you take computers for granted. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. More niche applications begat niche machines, and a number of them are on display in this film that the Computer History Archives Project released last month. Aside from the File-o-matic Desk, the Addressograph, or the Sound Scriber, there a number of other devices that give us a peek into a bygone era.

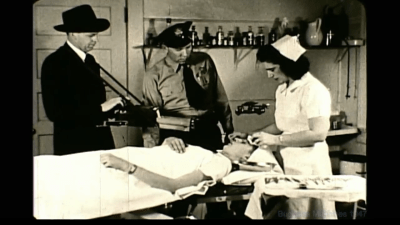

One machine that’s still around, although in a much computerized form, is the stenograph. Not so popular these days is the convenient stenograph carrier, allowing a patient’s statement to be recorded bedside in the hospital immediately after a car accident. Wire recorders were all the rage in 1947, as were floppy disks (for audio, not data). Both media were used to time-shift dictation. Typing champions like Stella Pajunas could transcribe your letters and memos at 140 WPM using an electric typewriter, outpacing dot matrix printers but a snail’s pace compared to a laser jet.

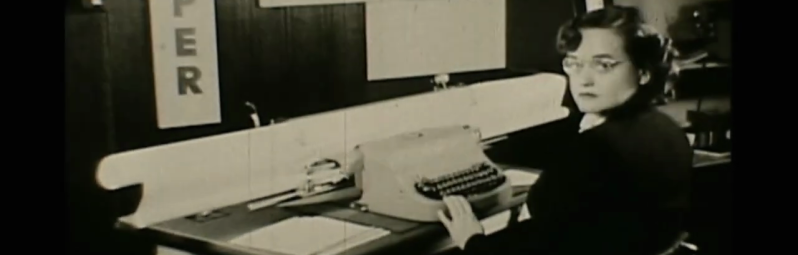

Typing Ten Feet Wide

Before the IBM Selectric and its changeable font balls, there was the Varityper. It was a sophisticated typewriter supporting multiple fonts and proportional spacing. An unusual one is shown here, used for typing notes on engineering drawings and maps up to ten feet wide, in various fonts and sizes.

Chinese Typewriter is Innovative but Flops

Next we have the IBM electronic Chinese typewriter, the invention of IBM Rochester engineer [Kao Chung-Chin] (US patent 2,412,777, Dec 1946). In his design, [Kao]’s solution to handling thousands of Chinese glyphs is not a monster keyboard. Rather, he requires the typist to enter a four-digit code using a modest number of keys. In modern terms, this would be like typing your document using Unicode values on a numeric keypad. Despite this impediment, IBM worker [Lois Lew] managed a respectable 45 WPM on this behemoth. And unlike the typewriter project, which was cancelled, [Lois] is still alive and kicking in Rochester. She recently connected with Stanford University professor [Thomas Mullaney] who is a researcher in Chinese history and focuses on typewriters. You can read his piece on this typewriter’s history and [Lois]’s involvement with the project in this article he wrote back in May.

Feeling Really Old

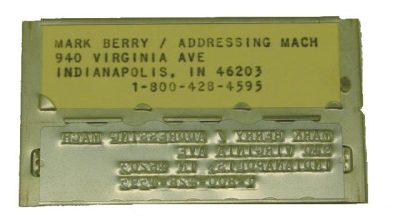

I recognized, and actually used a few of the items featured in this film. My father’s workplace, where I would sometimes hang out after school, had a few of these machines back in the 1970s. The most spectacular was the Addressograph system, used to prepare mailings for newsletters, post cards, etc. It was basically a mechanical database. Each person was represented by a special card, prepared by a Graphotype machine, a specialized typewriter that embosses text on small metal plates, not unlike a dog-tag. The card was actually a frame, which held the embossed plate, a piece of card stock with the information typed by conventional means, and a series of slots along the top of the card which could hold metal tabs. These tabs denoted different user-defined categories. In an engineering company, for example, you could designate tab positions for each department, for each building, for each project team, etc. The entire company roster is now contained in one or more filing drawers, each about the size of an old-fashioned library card catalog drawer.

When you want to send out a letter to all the mechanical engineers working in the Poughkeepsie office, the operator would set up the Addressograph machine accordingly. The stack of cards from each drawer is slid into the feed rack, and each card is conveyed one-by-one through the machine for printing. Only those cards whose tabs match the setup are printed onto the envelopes. Cards not selected for the mailing would be passed over. After some time, my Dad realized that each drawer had its own quirks and temperament, so he gave each of them names.

Pedro could always be counted upon to misbehave.

These machines required a bit of maintenance to keep running, but they were built like a tank. The ones I encountered as a teenager were purchased in the late 1940s and kept operational until the early 1980s, when other affordable options became viable. That seems like a long time today, when office equipment has lifespans measured in years not decades. Despite getting the job done, such single-purpose specialized office machines have all but vanished from the typical office these days. And no wonder — almost every function featured in this film can be done today with a desktop computer and a multifunction printer / scanner.

Check out the the video below the break. Are you still using any obsolete office equipment today? Let us know in the comments below.

0 Commentaires