In our no-nonsense journey through the world of audio technology we’ve so far have looked at digital audio and the vinyl disk recording. What’s missing? Magnetic tape, the once-ubiquitous recording medium that first revolutionised the broadcast and recording industries in the mid-20th-century, and went on to be a mainstay of home audio before spawning the entire field of personal audio. Unless you’re an enthusiast or collector, it’s likely you won’t have a tape deck in your audio setup here in 2021 and you’ll probably be loading your 8-bit games from SD card rather than cassette, but surprisingly there are still plenty of audio cassettes released as novelties or ephemeral collectables.

The Device That Made The Sound Of The Latter Half Of The 20th Century

The first magnetic recordings were made directly on metal wires, but metal fatigues as it bends. By coating a flexible plastic tape in ferrous particles, the same simple technique of laying down an audio signal as variations in the magnetic field could be made smaller, lighter, and more robust. But the key to the format’s runaway success is the technical advancements that differentiate those 1950s machines from their wire recorder ancestors.

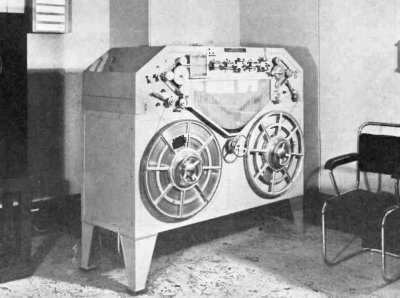

Whether it is a humble cassette recorder or a top-end studio multitrack, all tape recorders are very similar. There are two reels that hold the tape: the playback reel that houses the recording, and the take-up reel that stores the tape as it plays in the machine. The take-up reel is lightly driven to run faster than the tape speed, and the playback reel has a slight braking force to keep the tape under tension at all times.

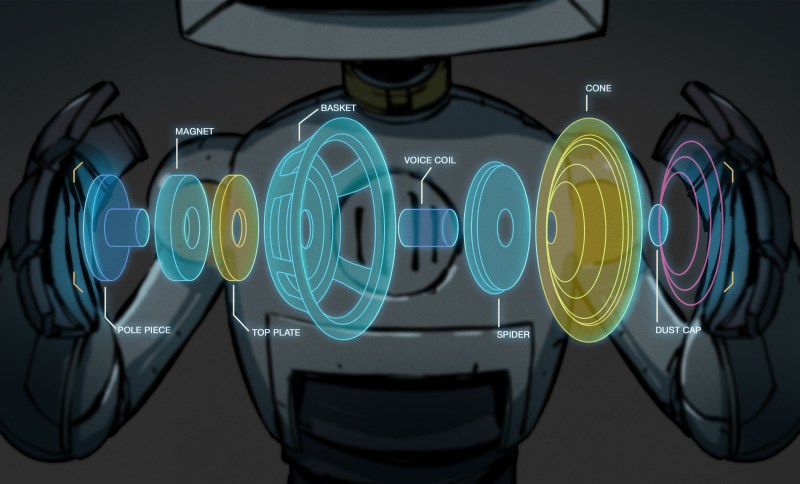

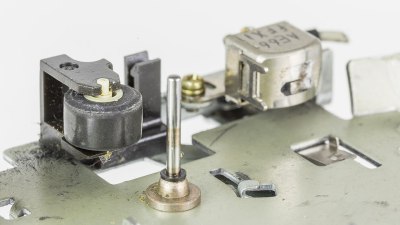

If the tape is simply pulled past the head by the force on the take-up reel, it will run at a variable speed dictated by the power on the reel and the radius of the tape spooled upon it. It’s important that the tape speed be kept constant, and this is achieved by clamping it between a constant-speed rotating metal roller and a rubber one. This pinch roller regulates the speed, with tape tension maintained on both sides of it by the reel drives. Before the tape passes through the pinch roller, it passes by two or three magnetic read and write heads. First contact is with an erase head, followed by the record and playback heads. In some machines the record and playback are performed by the same head. The heads have adjustable azimuth, which is set such that the gap between the head’s poles is perpendicular to the edge of the tape.

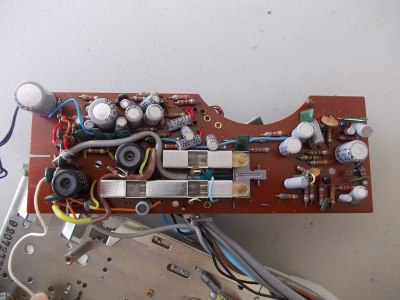

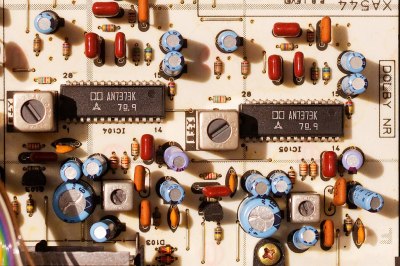

The recording and playback heads are both connected to audio amplifiers. In some inexpensive machines these two amplifiers are the same physical circuit reversed by means of the record/playback switch, but in high quality recorders they will be separate. The erase head is driven by a high-frequency AC signal when recording, with the intent of removing and overwriting any previous recordings.

Magnetic tape is not a linear medium, meaning that the degree to which it can be magnetised is not linearly proportional to the magnetic field applied. But it does have a range where it’s approximately linear, leading engineers to seek ways to keep the audio recording into the linear region and vastly lower the distortion. Originally they used a DC bias with a fixed DC current flowing through the recording head, but later designs used an AC bias in which a high-frequency AC signal several tens of kHz higher than the audio signal is recorded alongside it, the AC being inaudible on playback but having the effect of providing a constant recording level to keep within the linear region of the tape’s magnetic properties. The AC bias is derived from an oscillator that also provides the drive for the tape erase head, and whose frequency and level are set to different values depending on the type of tape medium in use. Different magnetic materials have been used in tape media including iron oxide, chromium dioxide, and finely divided iron particles, and each of those has different magnetic properties and requires a different bias.

Magnetic tape is an inherently noisy medium, to the extent that the whooshing sound of background noise is clearly audible in a tape recording. If you’re familiar with Dolby Laboratories it may be through their surround-sound encoding for movie theatres and home cinema systems, but it was in analogue recording noise reduction systems that they started. The original Dolby system was a set of filters applying companders (amplifiers with a logarithmic response intended to increase the dynamic range) to different frequency bands, which when reversed had the effect of reducing the high frequency noise component of the resulting signal. The consumer version of this was called Dolby B, and it was a standard feature of tape recording equipment from the early 1970s onwards.

Which Tape Is The One For You?

For the collector, ther have been a multitude of esoteric tape cartridges and cassettes over the decades, but for the purposes of a Hi-Fi system it’s likely that only two formats will be of interest. The reel-to-reel was the original tape recorder, having as its name suggests a pair of open reels of tape. Consumer and lower-end professional reel-to-reel machines used 1/4 inch wide tape running at a variety of speeds, from 15 inches per second for broadcast quality to 7.5 inches per second as a normal workaday recording medium, and 3.25 inches per second for speech recording. Its extreme ease of editing with a razor blade to cut the tape before splicing with special sticky tape made it a revolution in the broadcast world, and some of us were still doing this in the 1990s.

Perhaps you’ll be more familiar with the cassette tape, a format developed at Philips in the 1960s as a dictation medium but which due to its popularity was developed into a Hi-Fi medium and then through the success of Sony’s Walkman, to the genesis of portable music players. This format takes the two reels, miniaturises them, and encases them in a plastic cassette, with a 0.15 inch wide tape containing four tracks in two stereo pairs moving at 1 7/8 inches per second. That the format could be developed to the point at which such a low tape speed could provide what eventually became a high quality system is a tribute to the work of the many engineers at the competing audio companies of the era who pushed it to its limit.

If you hadn’t looked at a tape recorder much more than as a novelty owned by an older relative, then we hope you’ve found something of interest. Perhaps you’d like one for your own stack, and surprisingly it’s still possible to buy brand new cassette recorders in 2020. But while cassette player mechanisms were once manufactured to a very high standard by high-end manufacturers for their own products, now there seems to be only a very small number of different mechanisms manufactured that appear in all new cassette players on the market. There’s a top-loading mechanism that appears in all AliExpress Walkman clones, as well as a slot-loading one that can be found in whatever car cassette players remain available. The Internet will tell you that they are clones of mechanisms made by a Japanese company called Tanashin, makers of budget mechanisms until 2009, and the general consensus is that they are of a very low quality. We would suggest trawling the auction sites and Goodwill stores for a good quality Hi-Fi deck from the late 1980s or early 1990s, buying a replacement belt kit, and learn how to set up its tape head azimuth.

Tape recording is obsolete and maybe even irrelevant for audio in 2021; why on earth would you find it of interest? Its cultural impact. It’s fair to say that tape defined the sound of popular musical production since the 1950s. Music moved from set pieces that could be performed live, to studio production masterpieces that depended on months of work to produce a sound unachievable through instruments on their own, and this is because of tape. Before the (tape) Walkman, listening to recorded music was a sit-down-in-the-living-room affair, and now we take portable music for granted. Perhaps a more accessible legacy lies in a more human plane, how many of you have assembled a mixtape? Send your beloved a hand-crafted tape of your current musical choices, with a hand-drawn sleeve for the cassette case, and if you receive one in return play it to death. “I assembled a Spotify playlist for you” just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

After this sojourn into obsolete analogue audio we’ll be back on track with our next installment, and this time it’s getting right to the heart of some of the audio world’s more questionable claims. We’re going to look at cables.

0 Commentaires