It’s often said that the wheels of government turn slowly, and perhaps nowhere is this on better display than at NASA. While it seems like every week we hear about another commercial space launch or venture, projects helmed by the national space agency are often mired by budget cuts and indecisiveness from above. It takes a lot of political will to earmark tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars on a project that could take decades to complete, and not every occupant of the White House has been willing to stake their reputation on such bold ambitions.

In 2019, when Vice President Mike Pence told a cheering crowd at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center that the White House was officially tasking NASA with returning American astronauts to the surface of the Moon by 2024, everyone knew it was an ambitious timeline. But not one without precedent. The speech was a not-so-subtle allusion to President Kennedy’s famous 1962 declaration at Rice University that America would safely land a man on the Moon before the end of the decade, a challenge NASA was able to meet with fewer than six months to spare.

Unfortunately, a rousing speech will only get you so far. Without a significant boost to the agency’s budget, progress on the new Artemis lunar program was limited. To further complicate matters, less than a year after Pence took the stage in Huntsville, there was a new President in the White House. While there was initially some concern that the Biden administration would axe the Artemis program as part of a general “house cleaning”, it was allowed to continue under newly installed NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. The original 2024 deadline, at this point all but unattainable due to delays stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, has quietly been abandoned.

Unfortunately, a rousing speech will only get you so far. Without a significant boost to the agency’s budget, progress on the new Artemis lunar program was limited. To further complicate matters, less than a year after Pence took the stage in Huntsville, there was a new President in the White House. While there was initially some concern that the Biden administration would axe the Artemis program as part of a general “house cleaning”, it was allowed to continue under newly installed NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. The original 2024 deadline, at this point all but unattainable due to delays stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, has quietly been abandoned.

So where are we now? Is NASA in 2022 any closer to returning humanity to the Moon than they were in 2020 or even 2010? While it might not seem like it from an outsider’s perspective, a close look at some of the recent Artemis program milestones and developments show that the agency is at least moving in the right direction.

The Shakedown Cruise

A key component of the Artemis program is the Space Launch System (SLS), a gargantuan rocket derived from Space Shuttle hardware. But unlike the reusable Shuttle, there will be no attempt to recover any of the hardware in-between flights. Each SLS will only fly on a single mission, at the end of which it will crash into the ocean downrange like the Saturn V that took Apollo to the Moon.

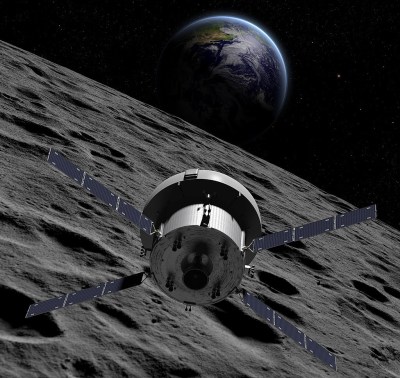

After years of delays, the first operational SLS was recently rolled out to Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39B for final checks before embarking on its debut mission: Artemis I. When it launches this summer, the megarocket will accelerate an uncrewed Orion capsule towards the Moon, where it will orbit for six days to perform checks on the vehicle’s systems, run various experiments that will support subsequent crewed missions aboard Orion, and deploy an array of small CubeSats.

After years of delays, the first operational SLS was recently rolled out to Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39B for final checks before embarking on its debut mission: Artemis I. When it launches this summer, the megarocket will accelerate an uncrewed Orion capsule towards the Moon, where it will orbit for six days to perform checks on the vehicle’s systems, run various experiments that will support subsequent crewed missions aboard Orion, and deploy an array of small CubeSats.

In total the mission will run for a little over 25 days, which will give engineers time to collect data on the radiation environment inside the Orion capsule during deep space flight. Dosimeters inside the cabin will record how much radiation a human crew would have been exposed to in a standard “shirtsleeves” environment, while a second set will quantify the effectiveness of a wearable radiation-shielding vest currently in development by Lockheed Martin and StemRad.

Should everything go to plan, Artemis I will be followed by the Artemis II mission no earlier than 2024. This 10-day mission will see four astronauts make a flyby of the Moon, much like the Apollo 8 “dry run” in 1968. No landing will be attempted, but it will mark the first time humans have traveled beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Preparing for Touchdown

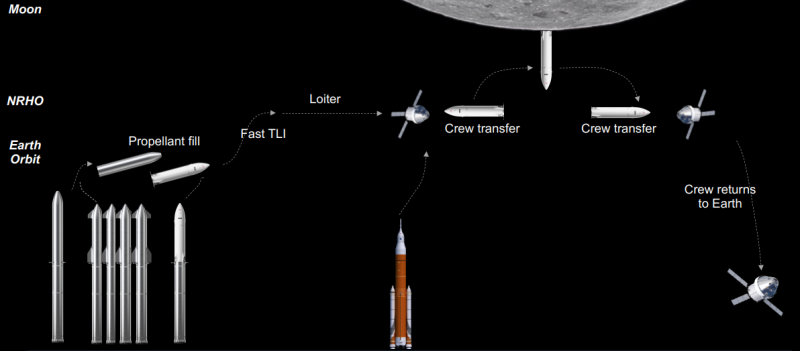

According to the current plan, humans won’t actually step foot on the Moon until Artemis III, which is slated for no earlier than 2025. Astronauts will launch on the SLS and ride the Orion to lunar orbit, where a customized SpaceX Starship will already be there waiting for them. Two crew members will transfer to the Starship, which will land on the surface and serve as their base of operations for approximately one week. After the surface operations are complete, the Starship will liftoff from the Moon, meet the Orion capsule in orbit, and the reunited crew will return back to Earth.

Standing 50 meters (164 feet) tall, Starship is a very different vehicle than the spidery Apollo Lunar Excursion Module (LEM). It will very literally be like landing the Statue of Liberty on the surface of the Moon, and then launching it back into space in one piece. The massive scale of Starship offers tantalizing possibilities, but also poses considerable challenges. For example, how exactly are astronauts supposed to make “one small step” when the hatch is 12 stories up?

NASA recently released a document that goes over some of the logistical challenges of the Human Landing System (HLS), and how they were working with the teams at SpaceX to convert Starship into a multi-purpose lunar exploration vehicle. That includes a large open elevator that can safely lower astronauts and equipment from the nose of Starship down to the lunar surface. The crew will also need a large airlock so they can enter and exit Starship without decompressing the entire vehicle as was done on the relatively tiny LEM.

None of these features were a secret, or unexpected. Indeed, even the earliest renders of the lunar Starship showed it would have some kind of elevator to descend down the side of the hull. But these photographs of actual prototype hardware being tested shows that we’re not just talking about a concept anymore — the next vehicle to take humans to the Moon is actively under construction.

The More The Merrier

Initially, SpaceX was the only firm to secure a contract from NASA to build an Artemis lunar lander. But some, including Congress, weren’t thrilled with America pinning its triumphant return to the Moon on just one company. Naturally it’s too late to have any of them ready to go by 2025, but as Artemis is supposed to pave the way towards long-term exploration and habitation of our nearest celestial neighbor, there’s plenty of room for other companies to develop additional landing capability.

As such, NASA announced earlier this month that they will be looking for commercial partners to develop vehicles for surface operations after Artemis III. The plan is to have the Lunar Gateway station in operation by then, so the contract is specifically looking for vehicles that could ferry astronauts and cargo between the surface and the orbiting facility. In this arrangement, just like with the Starship, the SLS and Orion would still be required to get crews to and from the Moon.

There’s been plenty of debate about the necessity of the expensive booster, which it’s now estimated will cost taxpayers $4 billion per mission, in the face of increasingly capable commercial launch providers. But it seems clear that NASA, or at least those calling the shots from above, want to make sure there’s a niche cut out for it beyond the currently slated Artemis missions.

0 Commentaires