A huge part of the work our community does, aside from making things and doing a lot of talking about the things we’d like to make, involves repair. We have the skills to fix our own stuff when it breaks, we can fix broken stuff that other people throw out when it breaks, and we can fix broken stuff belonging to other people. As our consumer society has evolved around products designed to frustrate repairs and facilitate instead the sale of new replacements for broken items this is an essential skill to keep alive; both to escape having to incessantly replace our possessions at the whim of corporate overlords, and to fight the never-ending tide of waste.

Repair Cafés: A Good Thing

So we repair things that are broken, for example on my bench in front of me is a formerly-broken camera I’ve given a new life, on the wall in one of my hackerspaces is a large screen TV saved from a dumpster where it lay with a broken PSU, and in another hackerspace a capsule coffee machine serves drinks through a plastic manifold held together with cable ties.

We do it for ourselves, we do it within our communities, and increasingly, we do it for the wider community at large. The Repair Café movement is one of local groups who host sessions at which they repair broken items brought in by members of the public, for free. Their work encompasses almost anything you’d find in a home, from textiles and furniture to electronics, and they are an extremely good cause that should be encouraged at all costs.

For all my admiration for the Repair Café movement though, I have chosen not to involve myself in my local one. Not because they aren’t a fine bunch of people or because they don’t do an exceptionally good job, but for a different reason. And it symbolically comes back to an afternoon over thirty years ago, when sitting in a university lab in Hull, I was taught how to wire a British mains plug.

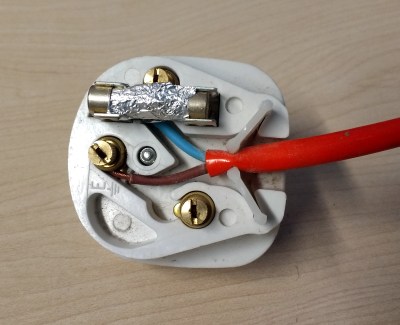

It Starts With A Mains Plug

Of course I already knew how to wire a mains plug as I’d been doing it when repairing broken electrical appliances for years at that point, but the point was that as an electronic engineering student I was being taught to do it properly. In fact during those three years training I learned a lot more about electrical safety than just how to wire a plug, I came away with plenty of high-voltage experience as well as a lot of electrical safety testing under my belt outside the realm of my course as I and my friends tried to ensure that the early-90s ravers we were setting up equipment for wouldn’t be electrocuted. If you can remember the rave era, you weren’t really there, man!

So I can do high-voltage electrical work, and I’ve been trained to do it safely. As i write this I’m surrounded by equipment on which I’ve done just that. But here’s the crux of my problem, as someone who’s been trained to do it I have a responsibility on my shoulders to get it right.

In other words, should someone later electrocute themselves on something that I repaired, I bear a greater liability than someone with no training, because I’m supposed to know how to do things safely. And since I may not know what else lurks in a piece of older mains electrical gear, I’ve reluctantly decided that it probably presents a risk and thus I’d better not participate in a Repair Café. It goes against a lot of what I personally stand for, but it’s my butt on the line if something goes wrong.

Among Hackaday’s readership will be people who participate in Repair Cafés, run them, or are involved in the wider Repair Café movement. I’d like to ask them whether my concerns above are valid or whether I’m worried about nothing, and indeed about the wider question of repair and liability. Repair Café or not, that’s the question!

0 Commentaires