NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope is arguably the best known and most successful observatory in history, delivering unprecedented images that have tantalized the public and astronomers alike for more than 30 years. But even so, there’s nothing particularly special about Hubble. Ultimately it’s just a large optical telescope which has the benefit of being in space rather than on Earth’s surface. In fact, it’s long been believed that Hubble is not dissimilar from contemporary spy satellites operated by the National Reconnaissance Office — it’s just pointed in a different direction.

There are however some truly unique instruments in NASA’s observational arsenal, and though they might not have the name recognition of the Hubble or James Webb Space Telescopes, they still represent incredible feats of engineering. This is perhaps best exemplified by the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), an airborne infrared telescope built into a retired airliner that is truly one-of-a-kind.

There are however some truly unique instruments in NASA’s observational arsenal, and though they might not have the name recognition of the Hubble or James Webb Space Telescopes, they still represent incredible feats of engineering. This is perhaps best exemplified by the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), an airborne infrared telescope built into a retired airliner that is truly one-of-a-kind.

Unfortunately this unique aerial telescope also happens to be exceptionally expensive to operate; with an annual operating cost of approximately $85 million, it’s one of the agency’s most expensive ongoing astrophysics missions. After twelve years of observations, NASA and their partners at the German Aerospace Center have decided to end the SOFIA program after its current mission concludes in September.

With the telescope so close to making its final observations, it seems a good time to look back at this incredible program and why the US and German space centers decided it was time to put SOFIA back in the hangar.

Eye In the Sky

By making its astronomical observations while flying through the stratosphere at an altitude of approximately twelve kilometers (40,000 feet), SOFIA is literally and figuratively a middle ground between ground and space based telescopes. Its operational altitude means the telescope is above the vast majority of atmospheric water vapor that would otherwise block certain infrared frequencies from reaching the Earth’s surface, while its ability to be regularly serviced and upgraded gives it the sort of scientific flexibility that would normally be associated with an observatory on the ground.

The key to the SOFIA program is an aircraft large enough to carry the telescope, along with its instrumentation and the personnel to operate it, up to the required altitude for stable, long-duration flights. In this case, it’s a Boeing 747SP wide-body airliner that originally started its career with Pan Am back in 1977.

The key to the SOFIA program is an aircraft large enough to carry the telescope, along with its instrumentation and the personnel to operate it, up to the required altitude for stable, long-duration flights. In this case, it’s a Boeing 747SP wide-body airliner that originally started its career with Pan Am back in 1977.

This special “SP” variant of the iconic 747 was specifically engineered to fly longer, faster, and higher by removing a section of the fuselage and performing other mass-saving modifications. Built in relatively limited numbers specifically for flights between New York and the Middle East, the airframe used for SOFIA is one of only four 747SPs still flying.

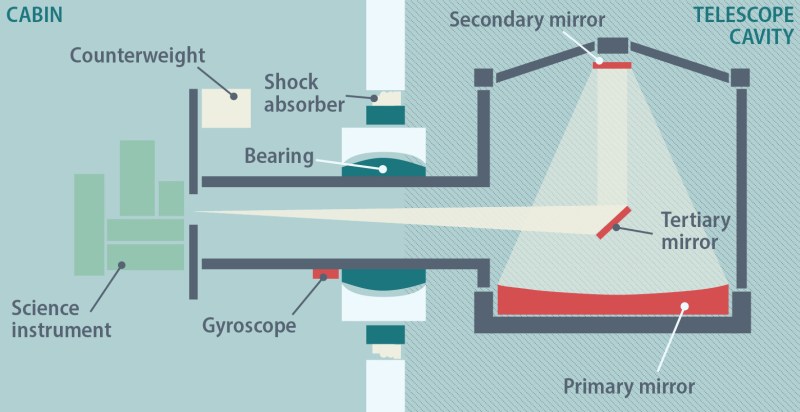

Considerable structural modifications were required for the 747SP to carry the 17 metric ton (38,000 lbs) telescope, but certainly none more obvious than the large door that can be opened during flight to expose the 2.7 m (8.8 ft) primary mirror. To prevent an inrush of wind when the door is open, which would introduce unacceptable vibrations in the optics, a pronounced “hump” was added to the rear of the fuselage to redirect the high-speed airflow before it hits the opening. Some turbulent air does invariably enter the chamber, but it can be compensated for using the telescope’s mount, which uses a combination of pressurized oil bearings, counterweights, gyroscopes, and magnetic torque motors to stabilize and aim the instrument.

Powerful Competition

The SOFIA telescope is by far the largest ever to be mounted in an aircraft, a record which will almost certainly never be broken. Even still, its primary mirror is dwarfed by the 6.5 m (21 ft) reflector of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), NASA’s new flagship infrared telescope that is just days away from coming online. While it’s difficult to directly compare the two observatories and their capabilities, there’s no question that the JWST represents the future of infrared astronomy. At the same time, SOFIA has faced criticism over the last few years over how little scientific data it has been able to collect relative to its high development and operational costs.

While the JWST largely makes SOFIA redundant, that’s not to say the scientific community won’t mourn its loss. Not only is SOFIA capable of observing a much wider range of IR frequencies, but its unique ability to target the moon led directly to the 2020 confirmation of water on the sunlit lunar surface. It can also be upgraded over time to make observations with instruments that today might not even exist, whereas the JWST is too far from Earth to ever receive the sort of incremental upgrades that Hubble did.

Put simply, there’s a valid need for an observatory like SOFIA. But unless NASA can figure out a cheaper way to build and operate one, it might be a scientific niche that goes unfulfilled.

0 Commentaires