Traveling through mainland Europe on a British passport leads you to several predictable conversations. There’s Marmite of course, then all the fun of the Brexit fair, and finally on a more serious note, beer. You see, I didn’t know this, but after decades of quaffing fine ales, I’m told we do it wrong because we drink our beer warm. “Warm?”, I say, thinking of a cooling glass of my local Old Hooky which is anything but warm when served in an Oxfordshire village pub, to receive the reply that they drink their beers cold. A bit of international deciphering later it emerges that “warm” is what I’d refer to as “cold”, or in fact “room temperature”, while “cold” in their parlance means “refrigerated”, or as I’d say it: “Too cold to taste anything”. Mild humour aside there’s clearly something afoot, so it’s time to get to the bottom of all this.

Too cold to taste anything

Should you walk into a British pub, assuming it’s a good one you’ll see a range of beers on tap. There will be the tall polished levers of the hand pumps delivering the local ales, and there will be at one end of the bar a shiny silver pressure keg dispenser or two with a few mass-market beers. These usually come out of the tap refrigerated like my continental friends would expect, and invariably include the usual highly-advertised pilsener-style lagers. It’s on that bar then that you’ll see in microcosm what lies behind this great beer divide, and the clue came in the names “ale”, and “lager”. They are both beers, but their different styles reveal the story.

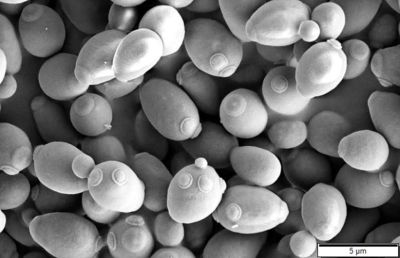

To make beer as we’d know it, one must boil up a quantity of malt and hops in water, add a yeast culture, and leave it to ferment for a while. That’s the basic recipe, but it’s in the myriad variations of ingredients and places that we find all the different styles we’ve come to know. Those ales and lagers both start out in the same way with malt and hops, but it’s in their yeast cultures that they diverge. Yeasts are a type of unicellular organism, and some varieties have the useful property of producing alcohol when the anaerobically consume sugar. Yeasts are all around us in the air so it’s entirely possible to make a beer using only whatever natural yeasts settle in the liquid without having to add a culture as such, this is the process behind the Belgian lambic beers.

It’s All In The Yeast

Because brewers value consistency of their product and hate to risk a batch going bad due to bacterial infection, most of them use a culture. This can be one specific to their brewery and bred across countless brews over years, or it can be one bred by a laboratory. The family of yeast varieties of interest to brewers are the Saccharomyces strains, and it’s two different varieties of Saccharomyces, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus, that are responsible for ales and lagers in turn. Even then it’s not as simple as just changing the yeast , because they each have very different properties. The ale yeasts ferment quickly at a high temperature and float on top of the liquid, while the lager yeasts ferment slowly and sink to the bottom. In there is the origin of the world “lager”, which refers to the practice of storing the beer in caves, or lagering it, as it completed its fermentation.

We now have some idea why ales and lagers are different types of beer, but why do Brits drink their ale at room temperature? Hackaday isn’t a beer review publication, no matter how much some of we scribes might like to spend more time in the pub, but it’s safe to describe a lager as having a lighter taste than an ale, and then to make the observation that the former tastes better when colder while the latter loses its flavour if it’s chilled. Hence those hand pumps in a British pub, and my perplexed Continental friends when faced with a British pint.

So we’ve got to the bottom of the warm beer question, but there’s a final injustice I must correct. Brits refer to any vaguely pilsener style beer as “lager” as if that were the only style of lager, while in fact lagers come in a huge range of styles of which pilsener is only one. Even then the pilseners we consume would probably shock a brewmaster from Pilsen to his core, such is their blandness. It’s clear that our Continental friends have much to learn about ales, but by Bacchus, we have a lot to learn about lagers!

0 Commentaires