Energy prices have been in the news more often than not lately, as has war. The two typically go together, as conflicts tend to impact on the supply and trade of fossil fuels.

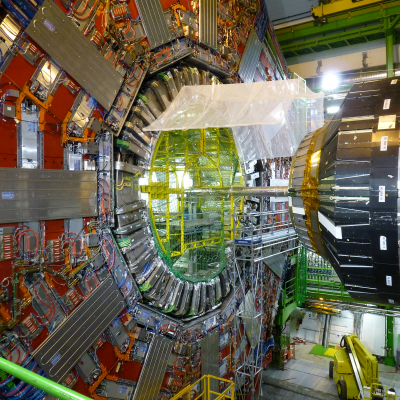

With Europe short on gas and its citizens contemplating a cold winter, science is feeling the pinch, too. CERN has elected to shut down the Large Hadron Collider early to save electricity.

Bill Shock

With Europe facing a dire situation this winter, CERN has agreed to a request from Électricité de France (EDF) to cut its electricity use going forward. The laboratory will cut back on its energy consumption for the rest of 2022 and into 2023 to help ease the load on France’s electrical grid.

The governing council of CERN ratified the plan on September 26. In 2022, CERN will close its operations two weeks early to help cut demand, calling a technical stop on 28 November. It will also scale back operations by 20% for 2023. This will primarily be achieved by closing four weeks early next year, stopping operations some time in mid-November. Start dates for CERN’s operations will remain the same in 2023 and 2024, with the lab getting major work underway again as scheduled in late February.

As a high-energy physics lab, CERN racks up significant energy bills even in a regular year. The lion’s share comes from the organization’s crown jewel, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and cools the particle accelerator’s superconducting magnets, which operate at a temperature of -271°C. To maintain that temperature, the LHC relies upon a 27-megawatt liquid helium cooling system. As it turns out, doing high-energy physics has high energy requirements. CERN draws around 200 megawatts during peak consumption periods, but this drops to just 80 megawatts during the quieter winter months.

In a typical year of normal operations, CERN uses around 1.3 terawatt-hours of electricity. As a comparison, the city of Geneva has a population of 200,000 people, and consumes 3 terawatt-hours per annum. Its electricity bill for 2022 is estimated to be around $89 million.

Cutting back on active research time will help save energy. However, a 20% cut to operational time won’t result in a 20% drop in energy use, due to maintenance requirements. For example, the LHC’s superconducting magnets must be kept cool, even when not in use.

CERN isn’t just cutting back on science to reduce its energy consumption. It will also take conventional measures, as well. On the lab’s campus, night time street lighting will be switched off where possible, and heating will be used one less week per year.

According to CERN, the decision to wind back operations hasn’t been made primarily over spiralling energy costs. Instead, measures are being taken out of concern for broader society. Much of Europe relies on natural gas for heating and electricity generation. With Russia continuing to wage war on Ukraine, those supplies are scarce. Fears abound over the coming winter, rolling blackouts, and potential supply shortages. Thus, the aim is to ensure that sufficient fuel resources are available to allow for crucial heating and electrical needs in people’s homes.

The early shutdown will mean that some experiments will no longer take place as scheduled. Those scientists who intended to use CERN’s facilities in the last two weeks of operations will instead be rescheduled for 2023. That also means there will be more competition for time on the facilities next year, in addition to the impacts of the further-reduced 2023 schedule.

Other science facilities are feeling the bite too, and some are more cost-sensitive than CERN. The German Electron Synchrotron has contracts that cover parts of its energy bill years in advance to avoid spikes. While 80% of the synchrotron’s bill is covered for 2023, the last 20% is still up in the air. At current prices, the organization cannot currently afford to cover the expense. Management is pursuing additional government funding, and exploring running some of its hardware at lower power settings as a compromise.

Much of CERN’s work is high-concept physics that doesn’t have a huge impact on our lives today. However, the research done there is the very sharpest of the cutting-edge, and is of profound value to humanity. For now, though, it is the prudent and noble thing to do to wind back operations as Europe faces a cold and uncertain winter ahead.

0 Commentaires