A culture in which it’s fair to say the community which Hackaday serves is steeped in, is electronic music. Within these pages you’ll find plenty of synthesisers, chiptune players, and other projects devoted to synthetic sound. Not everyone here is a musician of obsessive listener, but if Hackaday had a soundtrack album we’re guessing it would be electronic. Along the way, many of us have picked up an appreciation for the history of electronic music, whether it’s EDM from the 1990s, 8-bit SID chiptunes, or further back to figures such as Wendy Carlos, Gershon Kingsley, or Delia Derbyshire. But for all that, the origin of electronic music is frustratingly difficult to pin down. Is it characterised by the instruments alone, or does it have something more specific in the music itself? Here follows the result of a few months’ idle self-enlightenment as we try to get tot he bottom of it all.

Will The Real Electronic Music Please Stand Up?

Anyone reading around the subject soon discovers that there are several different facets to synthesised music which are collectively brought together under the same banner and which at times are all claimed individually to be the purest form of the art. Further to that it rapidly becomes obvious when studying the origins of the technology, that purely electronic and electromechanical music are also two sides of the same coin. Is music electronic when it uses an electronic instrument, when electronics are used to modify the sound of an acoustic instrument, when it is sequenced electronically often in a manner unplayable by a human, or when it uses sampled sounds? Is an electric guitar making electronic music when played through an effects pedal?

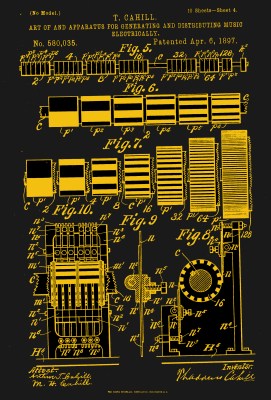

The history of electronic music as far as it seems from here, starts around the turn of the twentieth century, and though the work of many different engineers and musicians could be cited at its source there are three inventions which stand out. Thaddeus Cahill’s tone-wheel-based Telharmonium US patent was granted in 1897, the same year as that for Edwin S. Votey’s Pianola player piano, while the Russian Lev Termen’s Theremin was invented in 1919. In those three inventions we find the progenital ancestors of all synthesisers, sequencers, and purely electronic instruments. If it appears we’ve made a glaring omission by not mentioning inventions such as the phonograph, it’s because they were invented not to make music but to record it.

I Never Expected To Find Myself In 1940s Cairo

Even when we’ve established the origins of the technology, the same timeline doesn’t apply to the music itself. Player pianos spent their lives banging out the show tunes of the day, and even the decidedly modern sound of the theremin found its place as a classical music instrument playing in a similar role to the violin. Perhaps the biggest surprise in all this comes in the foundations of the music we’d recognise as being purely electronic coming as late as the middle of the 20th century. The fantastically complex compositions of Conlon Nancarrow for the player piano push the boundaries far past what we’re used to in a typical sequencer file today, but it’s in music concrète, the assemblage of found sounds enabled by the development of tape and wire recorders, that we find the progenitor of sampled music. Halim El-Dabh recorded The Expression of Zaar on a wire recorder in Cairo in 1944, and for those of us who hear it for the first time nearly eight decades later it’s lost none of its haunting qualities.

As a child of 1970s, the electronic music I grew up on that was part of the broadcasting soundscape and which forms the basis of what we’d recognise as electronic music today, sounded nothing like the 1950s avant garde of music concrète or the 1930s classical music of Clara Rockmore’s theremin. Perhaps the most significant event in electronic music history wasn’t a technological one but a social one then, because the happy confluence of engineers such as Robert Moog mastering the manipulation of sound fell alongside both the huge social change of the 1960s and the solid state revolution bringing the tech within reach of the common man.

By the time I was a teenager and then a student at the end of the 1980s the democratisation process of electronic music was complete, as I or any other kid could have a keyboard or a Commodore Amiga with a sampler on their desk. If the electronic music geeks where I grew up had a star in their midst it was Adamski, who shot to fame with a keyboard and sampler on a stand without the performance of a would-be rockstar, with his name on a reflective UK car number plate.

It would be another few decades before I’d learn the nuts and bolts of making music this way, because as with amateur radio my interest was in the tech not the usage. In researching this piece then I’ve gone over a lot of instruments and techniques that I already knew something about, but the real joy has come in listening to a bunch of obscure compositions from decades past I’d never otherwise have been fortunate enough to find. If you come to electronic music via the tech then I’d urge you to open up YouTube and get searching as I did. And if you’ve got a recommendation for something we should be listening to, put it in the comments. There’s way more to the history of electronic music than Popcorn!

0 Commentaires