When Mary Wallace “Wally” Funk reached the boundary of space aboard the first crewed flight of Blue Origin’s New Shepard capsule earlier today, it marked the end of a journey she started 60 years ago. In 1961 she became the youngest member of what would later become known as the “Mercury 13”, a group of accomplished female aviators that volunteered to be put through the same physical and mental qualification tests that NASA’s Mercury astronauts went through. But the promising experiment was cut short by the space agency’s rigid requirements for potential astronauts, and what John Glenn referred to in his testimony to the Committee on Science and Astronautics as the “social order” of America at the time.

Best of the Best

Before NASA could launch the first American into space, they had to decide what qualifications their ideal astronaut should have. An early idea that the agency should pursue thrill seekers such as race car drivers or extreme sport enthusiasts made a degree of sense given the immense risks involved, but it was ultimately decided that it would be more useful to the program if the occupants of these early spacecraft were experienced pilots with a science or engineering background. The hope was such individuals could give valuable feedback on the craft’s design and performance, and should the need arise, diagnose and potentially even fix an issue aboard the spacecraft themselves.

So in addition to meeting age and fitness requirements, applicants for Project Mercury needed to be college educated in a STEM subject and have experience flying jet aircraft. While there was little of what could traditionally be considered piloting to be done with these early spacecraft, having experience with the speed, altitude, and complexity associated with flying jets was seen as a important prerequisite.

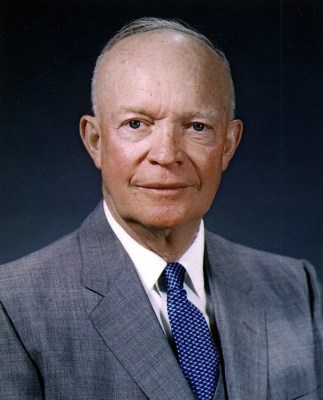

President Eisenhower, who himself learned to fly while in the Army, insisted that the final selection be further limited to active duty military test pilots; the idea being that such individuals would not only be in peak physical condition, but would be uniquely qualified to operate experimental vehicles and have a higher than average tolerance for risk.

While the extremely narrow criteria used to select the first Mercury astronauts was arguably justified, it did invalidate many excellent candidates. Legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager, who by all accounts should have been on the short list for NASA’s human space program, was out of the running as he never attended college. Neil Armstrong, who by this time had already piloted the X-15 to incredible speeds and altitudes, was also excluded from taking part as he hadn’t been in active duty since 1952.

The Right Stuff

While no NASA document specifically stated Project Mercury astronauts had to be males, the military service requirement made it impossible for a woman to make it through the selection process. There were certainly highly qualified female pilots in the United States, many who served their country by testing and transporting military aircraft as Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) during the Second World War, but they were all civilians. Of course this was hardly a surprise, as the Air Force wouldn’t start accepting female pilots for another 15 years.

This de facto discrimination didn’t go unnoticed by Jacqueline Cochran, a prominent female aviator and the head of the WASP program during the war. Cochran was not only a woman of considerable influence and wealth, but had a close personal friendship with William Randolph Lovelace, the chairman of the NASA Special Advisory Committee on Life Sciences. Convinced that women could be effective astronauts if they were simply given the chance, the two launched a privately funded project that aimed to put female volunteers through the same rigorous qualification process that NASA used for Project Mercury.

In 1960 Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb was invited to not only be the first woman to undergo the grueling tests, but to help identify other potential candidates for what was being called the First Lady Astronaut Trainees (FLATs). Having previously set endurance, altitude, and speed records, Cobb was an ideal choice for the program and was able to complete all three phases of NASA’s astronaut qualification exam. In fact, her results put her in the top 2% of candidates; a figure better than some of the men that were ultimately selected to fly on Project Mercury.

Encouraged by this early success, Lovelace and Cobb invited nineteen more women to go through the tests. Several of the candidates were well known in the air racing community, and all were accomplished pilots with more than 1,000 hours of flight experience.

An Experiment Cut Short

Twelve of the women who were invited to become FLATs passed the first phase of the trials at Lovelace’s clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico. However due to family and professional commitments only two candidates, Wally Funk and Rhea Hurrle, were able to continue on to the second phase of tests. This part of the program consisted of psychological and neurological examinations, including long periods of time spent in a sensory deprivation tank, where it was said the women outperformed the men by a considerable margin.

Unfortunately, neither woman was able to progress to the final phase of testing. Just a few days before the tests were set to begin at the Naval School of Aviation Medicine in Florida, the project was halted. Without the backing of NASA or the military, Lovelace was informed that the candidates would not be permitted to use the government facilities, aircraft, and equipment that was required to qualify the women.

In an effort to get Lovelace’s program the appropriate clearances, Jerrie Cobb and other FLATs petitioned President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. In July of 1962 a Congressional hearing was arranged, called the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts, that aimed to determine if gender discrimination played a part in NASA’s astronaut selection process.

When called to testify, astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter pointed out that regardless of how well the FLATs did in their physical and mental exams, none of them met the requirement of being an active duty military test pilot. But Glenn also admitted that NASA’s stipulation that candidates hold a STEM degree was actually waived in his case, as the agency was willing to count his engineering experience as an equivalent. In response, Congressman James Fulton of Pennsylvania questioned why NASA couldn’t establish a civilian flight experience equivalency for applicants who weren’t military pilots.

But to the surprise of many, the most damning testimony against Lovelace’s program ended up coming from the woman who helped start it, Jacqueline Cochran. While she maintained that exploring how the female mind and body fared against the rigors of spaceflight was a worthy endeavor, it was her opinion that the FLATs and the debate around them had become detrimental to NASA’s primary focus. If America was going to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon, Cochran said it was “natural and proper” that the nation’s astronauts be selected from “the group of male pilots who had already proven by aircraft testing and high speed precision flying that they were experienced, competent and qualified to meet possible emergencies in a new environment.”

A Lasting Impression

Despite Lovelace’s groundbreaking research, the hard work of the FLATs, and Jerrie Cobb’s passionate testimony before the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts, no women were selected for NASA’s Gemini or Apollo programs. In the end it was the Soviet Union that launched the first woman into space when Valentina Tereshkova conducted her solo mission in 1963; twenty years before NASA sent Sally Ride up on STS-7.

But the mark these women left on America’s space program was not forgotten. Eileen Collins, the first woman to pilot the Space Shuttle, invited the surviving FLATs to her launch in 1995. Now known in the media as the Mercury 13, the women were given a VIP tour of Kennedy Space Center and the Space Shuttle launch facilities.

Until Wally Funk accompanied Jeff Bezos on the first crewed flight of his company’s suborbital spacecraft, the history books would have recorded that none of the FLATs ever achieved their goal of traveling to space. The commercial mission has not only helped validate the work done by these pioneering women, but allowed Funk to blaze a new trail entirely. She might have missed the chance to be one of America’s first female astronauts, but at 82, she’s now set the record for being the oldest.

Though it might not be an official record, there’s no astronaut in the history of human spaceflight that has ever waited longer for the chance to put their training into practice. Congratulations, Wally Funk.

0 Commentaires