Identifying new species is key to the work of zoologists around the world. It’s an exciting part of research into the natural world, and being the first to discover a new species often grants a scientists naming rights that can create a legacy of one’s work that lasts long into the future.

Traditionally, the work of taxonomy involved capturing and preserving an example of the new species. This is such that it could be classified properly and studied in detail by scientists working now and in the future. However, times are changing, and scientists are beginning to identify new species on the basis of videos and photos instead.

Quality Matters

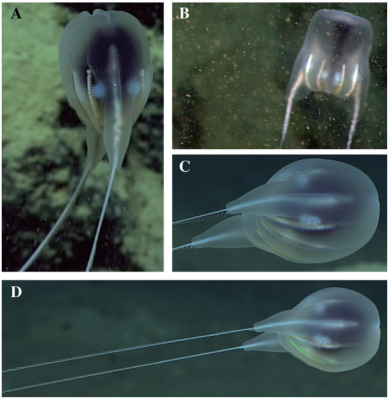

The first new species to be considered definitively identified and classified solely on the basis of video evidence is a comb jelly, or ctenophore, known by its scientific name of Duobrachium sparksae. Comb jellies are small carnivorous invertebrates that live in the sea, and are often as small as just a few millimeters in length. Found at a depth of 3,900 meters underwater, the new species was discovered on an expedition led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

No sample was captured for further study or preservation; instead, the high-definition video collected from a remotely-operated vehicle named Deep Discoverer was used as a basis for the findings instead. “We collected high-definition video and described what we saw,” scientist Mike Ford told The Guardian, adding “We went through the historical knowledge of ctenophores and it seemed clear this was a new species and genus as well. We then worked to place it in the tree of life properly.”

As for the unconventional methods used to describe the new species, NOAA scientist Allen Collins noted that “some inspect species descriptions have been done with low-quality imagery and some scientists have said they don’t think that’s a good way of doing things.” Acknowledging the team’s use of high-quality footage, he says that the work with Duobrachium sparksae has been relatively straightforward. “For this discovery, we didn’t get any pushback. It was a really good example of how to do it the right way with video,” he says.

Fundamentally, the team didn’t have much choice in the matter, anyway. “We didn’t have sample collection capabilities on the ROV at the time. Even if we had the equipment, there would have been very little time to process the animal because gelatinous animals don’t preserve very well; ctenophores are even worse than jellyfish in this regard,” said Collins, adding “High-quality video and photography were crucial for describing this new species.”

All in Agreement? Nay.

The issue of using photographic or video documentation for this purpose remains controversial, however. In 2016, a paper decrying the practice was signed by 493 taxonomists and specimen collection researchers, only to be rejected from publication in Nature in 2016. Later published elsewhere, the document references various submissions to the scientific literature dating back as far as 2007 in support of the practice.

The paper’s primary argument is that classifying species without capturing an actual specimen compromises “objectivity, replicability, and refutability.” Without a specimen that can be subjected to physical examination, the signatories of the paper are concerned that dubious claims of “new species” could flood in with little more than some photographs as evidence. As these can be readily doctored to a believable degree far more easily than a physical specimen, there are real fears this could cause major issues in the world of zoology going forwards.

Such methodology also leaves future scientists with little to work with, should they wish to look more closely at structures in the animal or particular features to relate the species to others or to perform more detailed taxonomical investigations. Photographs of a creature cannot reveal any new information under a microscope, nor provide genetic material for further investigation.

Not everyone is against the practice, however. An earlier paper takes a more balanced view, accepting the very real benefits of having an actual physical example of a creature when classifying a new species. In the eyes of the authors, this is very much the “gold standard.” The authors also discredit any notions that capturing examples of a species from the wild is deleterious in any real way, noting that when it comes to the vast majority of populations, capturing a handful of samples for scientific analysis is seldom of any real detriment.

However, it also notes the practical concerns of capturing, moving, and maintaining such samples, something which can frustrate the efforts of research scientists immensely. It also supports the contention that proper, high-resolution photography that captures necessary details can actually be more than enough to differentiate a new species from those already existing in the established taxonomy. This notion is supported through the naming of a “distinctive fly species” which the researchers dub Marleyimyia xylocopae, solely on the basis of photographic evidence of two living examples, as a fly captured by the scientists escaped before it could be preserved as a specimen.

As the paper notes, digital collections of high-quality images of all manner of species are becoming a mainstay in the world of zoology, and serve as a primary way that taxonomists and other researchers do their work. Thus, it seems likely that more flexibility on the capture and preparation of traditional dead specimens will be the way of the future. However, with the value that can be gained from the genuine physical article, many scientists will still be doing their utmost to collect such specimens wherever possible.

0 Commentaires