Robot arms and grippers do important work every hour of every day. They’re used in production lines around the world, toiling virtually ceaselessly outside of their designated maintenance windows.

They’re typically built out of steel, and powered by brawny hydraulic systems. However, some scientists have gone for a smaller scale approach that may horrify the squeamish. They’ve figured out how to turn a dead spider into a useful robotic gripper.

The name of this new Frankensteinian field? Why, it’s necrobotics, of course!

Working With Nature

Scientists and engineers have long held reverence for the achievements of the natural world. Tiny insects are capable of feats far exceeding those of our greatest robots, and can operate independently for days or weeks without ever needing to be plugged in. The intricate mechanical systems of spiders and beetles are beyond even our finest engineering to date.

Spiders are particularly impressive. They have eight legs of surprising strength, especially given their weight and power requirements. Rather than try to create something to match these capabilities from scratch, a group of researchers at Rice University decided to simply hack the spiders themselves.

Spider legs only have muscles for retraction, while extension is achieved via a hydraulic mechanism. In the spider’s body, a chamber filled with blood expands and contracts to control the movements of the creature’s legs. Each leg has a valve that allows the spider to control their movement individually. After death, all these valves open up and the spider’s hydraulic system loses pressure. This is what causes a spider’s legs to curl up after death.

The researchers realised that they could tap into this hydraulic system to extend and contract the spider’s legs at will. With a dead spider, all the individual leg valves typically fail open, so control is limited to extending or contracting all the legs at once. This causes the dead spider to act like a robot gripper, just like you might see on an skill tester arcade machine.

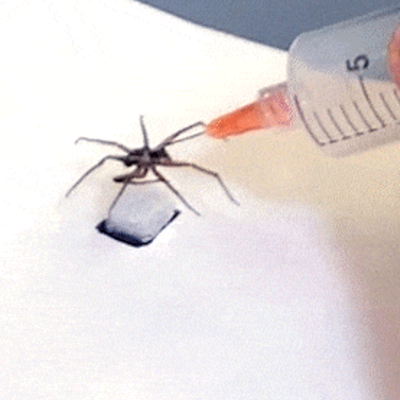

Researchers worked with wolf spiders, and began by euthanizing them in cold temperatures. A needle was then inserted into the spider’s body, and sealed with glue. This allowed the hydraulic passages inside the spider to be pressurized with air to extend the legs. Releasing the pressure lets the legs contract again into the curled up position.

Testing and Applications

The dead spiders are surprisingly robust. In testing, the group was able to get over 1,000 open-close cycles out of a single spider carcass. Some wear and tear was notable at the higher end of this range, which the team believes is primarily due to the dehydration of the spider body. Research is ongoing as to whether this problem can be solved with special polymeric coatings to keep the body from drying out.

Lifting power was also impressive. Wolf spider bodies were reliably able to lift 130% of their own body weight. Some bodies would exceed this figure by a great amount, too. Of course, variability is to be expected when working with a carcass as an engineering material.

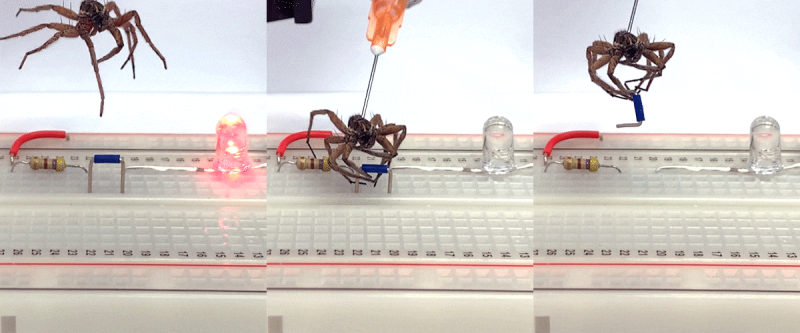

The team believes that dead spiders could serve as useful actuators for small-scale pick-and-place tasks. Demonstration from the team included using a spider gripper to pull a jumper out of an electronic breadboard. Other examples involved moving small objects and even lifting another spider. The benefit of the necrobotic gripper is that the spider’s eight legs are good at gripping objects of odd shapes and sizes.

The team believes that dead spiders could serve as useful actuators for small-scale pick-and-place tasks. Demonstration from the team included using a spider gripper to pull a jumper out of an electronic breadboard. Other examples involved moving small objects and even lifting another spider. The benefit of the necrobotic gripper is that the spider’s eight legs are good at gripping objects of odd shapes and sizes.

The team also cite the renewable nature of the necrobotic gripper. “The spiders themselves are biodegradable,” said Daniel Preston, assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering at Rice University. “We’re not introducing a big waste stream, which can be a problem with more traditional components,” he adds.

However, the necrobotic grippers as shown do have some limitations. A usable service life of 1,000 cycles is relatively low for a robotic gripper, particularly one to be used in a mass-production environment. There’s also a lot of variability in dead spider bodies that isn’t seen with regular engineered robotic components. Additionally, while the spider carcasses themselves are biodegradable, the needles, glues, and plastic fittings are not. Plus, the production of spider grippers is time-consuming, fiddly work. Then there’s the significant investment required in spider husbandry facilities.

The Future For Necrobotics

The research is compelling, and shows off reliable control of a stable spider carcass after death. It’s also much simpler than other insect-robotics projects that use electrodes inserted into cockroach brains for control. There’s no need to manipulate a living creature’s brain, or fight against its natural instincts to make it complete a given task.

However, the research would raise ethical hackles for some. It’s less troubling than electronically enslaving living beings, perhaps. Regardless, humans have always had strong feelings around the proper treatment and respect of mortal remains. Using spiders is likely to draw far less condemnation than if the same research were carried out with a mouse or hamster, for example. Try the same feat with a cat or a dog, and you might expect your lab to be closed with remarkable haste.

However, the research would raise ethical hackles for some. It’s less troubling than electronically enslaving living beings, perhaps. Regardless, humans have always had strong feelings around the proper treatment and respect of mortal remains. Using spiders is likely to draw far less condemnation than if the same research were carried out with a mouse or hamster, for example. Try the same feat with a cat or a dog, and you might expect your lab to be closed with remarkable haste.

Just to be clear, we don’t think you’ll be using a spider-based pick-and-place any time soon. But work in the field of necrobotics will likely teach us a lot about how the bodies of animals and insects work. They may also guide the development of our own robotic or biomechatronic creations. In any case, the quest for knowledge often presents us with strange and meandering paths to follow. And sometimes, just sometimes… those paths are covered in spiders.

0 Commentaires