The true measure of engineering success — or, at least, one of them — is how long something remains in use. A TV set someone designed in 1980 is probably, at best, relegated to a dusty guest room today if not the landfill. But the B-52 — America’s iconic bomber — has been around for more than 70 years and will likely keep flying for another 30 years or more. Think about that. A plane that first flew in 1952 is still in active use. What’s more, according to a love letter to the plane by [Alex Hollings], it was designed over a weekend in a hotel room by a small group of people.

A Successful Design

One of the keys to the plane’s longevity is its flexibility. Just as musicians have to reinvent themselves if they want to have a career spanning decades, what you wanted a bomber to do in the 1960s is different than what you want it to do today. Oddly enough, other newer bombers like the B-1B and B-2 have already been retired while the B-52 keeps on flying.

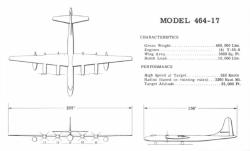

The original proposal for the plane came in 1948. Jet engines were new and not widely considered feasible for long-range bombers because of their fuel consumption. A three-person team from Boeing presented the recently-created Air Force with a plan to build a fairly conventional big bomber with prop engines and straight wings. The Air Force Colonel in charge of development was not impressed. After suggesting that swept wings and jet engines were the future, the team went back to the drawing board in a hotel room on a Thursday night. Their initial attempt was to simply put jet engines on the same airframe.

Not Good Enough

This wasn’t enough. So the team of four drew in two more people — still cramped in a hotel room and redesigned the airframe. The new design had a 185-foot wingspan with a 35-degree angle of the wings and no less than 8 jet engines. A local hobby shop supplied balsa wood, glue, some tools, and silver paint. The result: a 33-page proposal and a 14-inch model airplane. Four years later, that model plane looked almost exactly like the real article.

The plane was able to drop conventional or nuclear bombs and could fly around the world thanks to in-flight refueling. A global circumnavigation took just over 45 hours. Originally, the plane was meant to bomb from high altitudes out of reach of an adversary’s defensive weapons. Once the Soviet Union shot down Gary Powers in a high-altitude U-2, that seemed like a bad idea. But the plane’s versatility allowed it to morph into a low-flying bomber, skimming over targets as low as 400 feet — under the radar in most cases.

The old bird continues to change, proving it can even launch cruise missiles. With an engine refit replacing the 1960-era engine with modern ones, the plane will keep flying through the 2050s. Not bad for a weekend’s worth of work in a hotel room.

The Beauty of the Small Team

I can’t help but notice that things designed by small teams often have a lot to recommend them. Of course, I’m sure that some small team designs fail and then you just don’t hear about them. But consider, for example, the RCA 1800-series processors. By all accounts, these were the work of one person. It’s dated today, and wasn’t a huge commercial success, but if you use its assembly language you can tell that it was well thought out and with an overarching design goal. The CPU was moderately successful, especially in certain applications.

Forth and C started out as the brainchild of just a few people. Ada, on the other hand, was built by huge committees. Even the business community is recognizing that throwing more people on a problem isn’t always making the answer better.

Are They Wrong?

However, I have a slightly different opinion. I don’t think large teams are inherently bad. But consider this. When you set out to build your next robotics project by yourself, you know exactly what you have in mind and what’s important. So the end product is probably very satisfactory for your goal. That’s easy.

If you decide to work with a friend, what happens? Maybe you clash. Maybe you have different ideas and don’t clash, but in the end, nobody is totally satisfied. Or maybe, just maybe, you settle on a common set of goals and design principles and you end up with something good. That can happen in one of two ways. Either one person is very strong-willed and influences the other or — in the best case — collaboration allows both people to influence the other to arrive at a common shared set of goals and principles.

The problem is, even if those outcomes were equally probable, that’s still a 50% fail rate. In half the cases you just clash or do your own thing and don’t get a good result. But I submit that they aren’t equally probable. The strong-willed individual pairing with someone who will acquiesce is relatively rare and finding two people who can truly collaborate in a healthy way is even rarer. So the failure rate is actually more than 50%.

Now scale this up. When you add a third person, things are even less likely to align. Now try 40 or 100 people. Not only is it hard to build a consensus team, but it is also genuinely difficult to keep a large team on a common goal with common guiding principles. It takes a special kind of leadership to make that work, and that kind of leadership is very rare.

So my thinking is that big teams don’t have to be bad. But they do take a special kind of leader that is in woefully short supply. It also takes the right kind of members on the team. We’ve all seen giant open source projects that have strong leaders, and we’ve seen ones that have weak leaders. Nearly all of them have at least a few bad apples that further test that leadership. Leading is hard. There is a fine line between letting things run amok and micromanagement. Not to mention, each increase in size brings more complexity. Communication is harder between 100 people. Given enough people, some number of them are not going to like each other, and there is no way to avoid that.

Can you drive from New York to San Diego without a spare tire? You can. Is it worth trying? Probably not. Can you get a team of hundreds of people to design something that works well? Maybe. Is it worth trying? Only if there is no other choice. Ideally, it seems, the world would be built by individual craftspeople who create something true to their vision. But that’s not always possible. The next best thing is to stack the deck by keeping design teams as small as possible.

0 Commentaires