There was a time when putting an object into low Earth orbit was the absolute pinnacle of human achievement. It was such an outrageously expensive and complex undertaking that only a world superpower was capable of it, and even then, success wasn’t guaranteed. As the unforgiving physics involved are a constant, and the number of entities that could build space-capable vehicles remained low, this situation remained largely the same for the remainder of the 20th century.

But over the last couple of decades, the needle has finally started to move. Of course spaceflight is still just as unforgiving today as it was when Sputnik first streaked through the sky in 1957, but the vast technical improvements that have been made since then means space is increasingly becoming a public resource.

Thanks to increased commercial competition, putting a payload into orbit now costs a fraction of what it did even ten years ago, while at the same time, the general miniaturization of electronic components has dramatically changed what can be accomplished in even a meager amount of mass. The end result are launches that don’t just carry one or two large satellites into orbit, but dozens of small ones simultaneously.

To find out more about this brave new world of space exploration, we invited Nathaniel Evry, Chief Research Officer at Quub, to host last week’s DIY Picosatellites Hack Chat.

Quub is one of a new breed of companies that have sprung up recently which plan on leveraging small, low-cost, satellites to offer services which were once the sole domain of megacorps and governments. Specifically, they’re working on a constellation of microsatellites that will allow independent monitoring of the Earth’s natural resources.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the chat started off with a pretty straightforward question: what actually qualifies as a micro or pico satellite? It turns out the ever-exacting NASA has a set of guidelines which broadly breaks down the overall SmallSat category (spacecraft under 180 kilograms) down into the following classes:

- Minisatellite: 100 – 180 kg

- Microsatellite: 10 – 100 kg

- Nanosatellite: 1 – 10 kg

- Picosatellite: 0.01 – 1 kg

- Femtosatellite: 0.001 – 0.01 kg

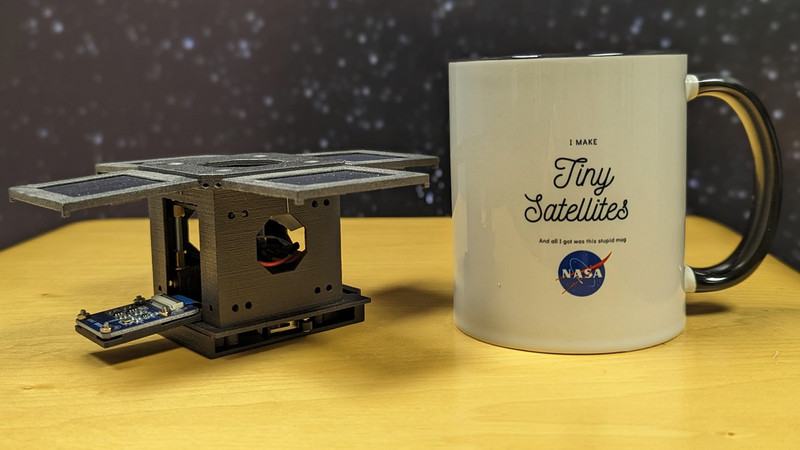

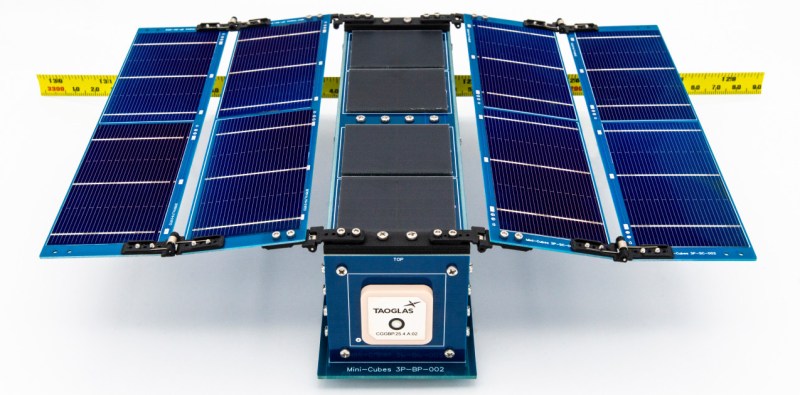

Outside of mass, there’s naturally the size and shape of the craft to consider. Here Nathaniel points out that there are various standards for modular satellite frames, but generally speaking they describe cubic and rectangular layouts which can be efficiently packed and dispensed. A common theme among these sort of SmallSats is that they will unfold into larger and more complex arrangements after deployment, often by extending solar array “wings” and antennas. Speaking about Quub specifically, Nathaniel says their primary platform is officially referred to as a 6p PocketQube, which measures roughly 50 mm x 100 mm x 200 mm.

But it’s more than just the size and shape of these satellites that benefit from standardization. In an effort to bring costs down even further, they commonly use commercial off-the-shelf components rather than the bespoke rad-hardened hardware which in decades past would have been a given for anything heading to orbit. Even if the final hardware does end up being a bit higher-end, Nathaniel says all of the prototyping work Quub has done so far has used the sort of hardware that you’d find in the average hardware hacker’s toolbox — including the Raspberry Pi and RP2040 microcontroller.

As the conversation moved towards the internal construction of SmallSats, Nathaniel mentioned that one of their internal design goals is to avoid wires if at all possible as they can become a liability during launch due to vibrations and high G-force. Boards are designed to connect to each other directly whenever possible, and when the use of wiring is unavoidable, special high-strength connectors are necessary. Though in a pinch “a lot of epoxy” is also an option.

With so many details on how Quub’s satellites are being designed and built, it’s little surprise that some in the chat were curious about whether the company plans on releasing any of their work as open source. The answer turns out to be a qualified yes; while their current design still involves some elements they aren’t ready to share publicly, Quub is in the process of releasing earlier generations of their platform under the MIT license.

Of course, despite the use of off-the-shelf components and 3D printed frames, we’re not quite at the point where your average hackerspace is throwing together a picosatellite with what’s in the beer fund. For one thing, the sort of space-rated Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers you’d want onboard your craft to provide position and velocity data aren’t exactly the kind of thing you can pick up from Micro Center. Similarly, while the Applied Ion Systems thrusters Nathaniel says Quub are using appear to be remarkably DIY-friendly, they still have five-figure price tags.

Arguably you could still fly without the niceties of thrusters or on-board navigation. After all, Sputnik did it. But then there’s still the small issue of getting your homebrew bird into space. While SpaceX and other commercial entities have shaved a few zeros off of what it costs to put a kilogram into orbit, it’s still a pricey proposition for an individual. But we’re getting there, and that’s extremely exciting. We’re now at the point now where small startups and universities can pull it off, and with a bit of luck, citizen scientists and hackers shouldn’t be too far behind.

We’d like to thank Nathaniel Evry for taking the time to talk about the exciting work happening at Quub and in the SmallSat community as a whole. Hosting a serious discussion about the future of DIY spacecraft is the sort of thing that we could once only have dreamt of, so we’re thrilled to have had the opportunity to make it happen. We’ll be keeping a close eye on Quub’s open source efforts, and wish them the best of luck as they venture out into the black.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.

0 Commentaires