Despite how hostile to life some parts of the Earth’s continents are, humanity has enthusiastically endeavored over the course of millennia to establish at least a toehold on each of them. Yet humanity has barely ventured beyond the surface of the oceans which cover around three-quarters of the planet, with human activity in these bodies of water dropping off quickly along with the fading of light from the surface.

Effectively, this means for all intents and purposes we have to this day not explored the vast majority of the Earth’s surface, due to over 70% of it being covered by water. As an ocean planet, much of Earth’s surface is covered by watery depths of multiple kilometers, with each 10 meters of water increasing the pressure by one atmosphere (1.013 bar), so that at a depth of one kilometer we’re talking about an intense 101 atmospheres.

Over the past decades, the 1985 discovery of Titanic’s wreck approximately 3.8 kilometer below the surface of the Atlantic, the two year long search for AF447’s black boxes, and the fruitless search for the wreckage of MH370 despite washed-on remnants have served as stark reminders of just how alien and how hostile the depths of the Earth’s oceans are. Yet with both tourism and mining efforts booming, will we one day conquer the full surface of Earth?

A Watery Grave

For most of human history, the oceans have been treated as essentially inaccessible, almost as if nothing that happens beyond a few hundred meters depth and the cessation of any fish species we might be interested in. Even so, long before the advent of deep-sea exploration, mythology has been rife with stories that in many cases contains at least a grain of truth. Much of these stories revolve around the sperm whale, its fantastical dives to depths of over 2 km and both their stomach contents and scars on their skin that seems to suggest the presence of enormous cephalopods, including the famous kraken that’d rise from the depths to drag entire ships back with it.

It wasn’t until a few hundred years ago that the first attempts were being made to determine the generally presumed to be unfathomable depths of the oceans at various points, along with the species that inhabit these depths. According to an 1843 theory proposed by Edward Forbes – called the Azoic hypothesis – the presence of life would diminish continuously, until the complete cessation of any life at a depth of 300 fathoms (550 meters). This was refuted by Michael Sars in 1850, who found life thriving at a depth of 800 meters, thus confirming papers published by Antoine Risso decades prior on deep-sea catches by fishermen.

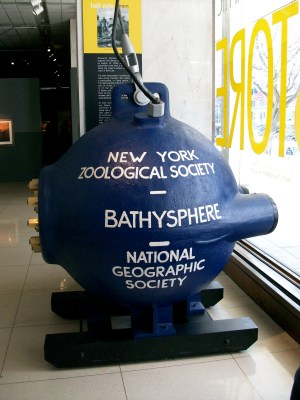

Up till that point, deep-sea exploration was performed solely by essentially dragging stuff out of it using nets and similar fishing implements, but this changed when in 1930 William Beebe and Otis Barton were the first to dive to a depth of 435 meters in their Bathysphere: a spherical, pressure-resistant vessel. In 1934 they’d set a new record with a depth of 923 meters, during which dives they observed the life visible just beyond the vessel’s portholes.

Lowered into the ocean by the ship that carried it, this vessel that may have appeared crude at first glance was nevertheless quite refined for the time, with a rudimentary life support system using cylinders of compressed oxygen to replenish the oxygen breathed in by the crew, and pans of soda lime and calcium chloride installed inside to scrub CO2 from the air after it had been exhaled.

The record set by the Bathysphere would remain until 1949 when Barton dove to 1,400 meters with the Benthoscope. At this point the race to develop ever better submersibles was fully on, and bathyscaphes (self-propelled, free-diving submersibles) appeared on the scene by the late 1940s. Being free-diving, these vessels do not require a massively long and heavy cable to winch them into and back out of the water, enabling much deeper dives.

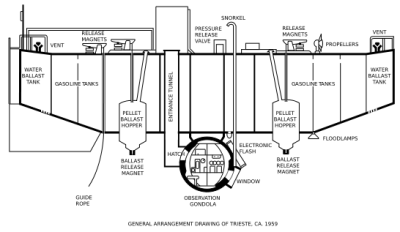

Redrawn from U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph NH 96807, General arrangement drawing of Trieste, ca. 1959.

By 1960, the bathyscaphe Trieste – piloted by Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh – reached the deepest known point on Earth’s surface: the Challenger Deep, located within the Mariana Trench of the Pacific Ocean. After some refinements to the depth measurements to take the alien conditions into account, it was determined that they had reached a depth of about 10,916 meters. Unexpectedly, both men were still able to communicate with the surface support ship USS Wandank, via the sonar/hydrophone voice communication system. Because of the immense distance, it took about seven seconds for a message to travel between the surface and the floor of the Challenger Deep.

Beyond Mythology

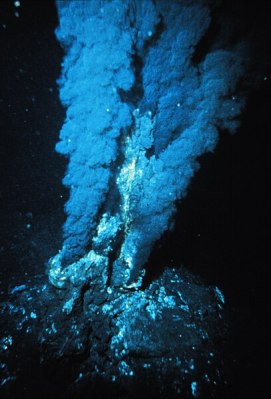

Along with the development of these newer and better submersibles, the mythology surrounding the depths of the ocean evaporated. What the photographs and videos recorded by both manned and unmanned deep-sea exploration vessels showed was a world completely devoid of the light which we as land-dwelling creatures hold for self-evident. In these depths, the electromagnetic radiation from our Sun does not penetrate, leaving everything in complete darkness. Even so, life found a way to create thriving ecosystems in an environment where

From deep-sea fish, to chemosynthetic organisms that live around hydrothermal vents and which use hydrogen sulfide synthesis as an alternative to the photosynthesis that powers life where the Sun’s rays still reach, the exploration of these hitherto unexplored depths have uncovered organisms and ecosystems that have changed our fundamental understanding of how life has formed and thrived on Earth. Even so, with how restricted our access is to these locations, scientific study is ongoing, with continuous new discoveries.

Along with the dissolution of the mythical depths came the inevitable push towards exploitation, both in the form of tourism and the mining of resources. However, what differentiates the lure of the untamed wilderness of Africa, America and other regions that were exploited in this manner over the past centuries, from the deep seas is that the latter might as well be the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. With no air to breathe, temperatures just above freezing and crushing pressures, even the challenge of climbing Mount Everest would seem to be a leisurely stroll in comparison.

With this in mind, can manned exploration of the depths ever be made safe enough for casual tourism, and will remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) be the way forward for deep sea mining?

Alien Worlds

An inescapable truth remains that the human body can only be kept alive at these depths through rather extreme measures. This has led within the off-shore industry to increasingly replace divers with underwater ROVs, These are remotely controlled robotic systems which can be either connected to a surface vessel with an umbilical cable that provides power and communication, or function with some level of autonomy. Beyond the obvious lack of a pressure vessel, these ROVs can be designed for any depth and any task, making them exceedingly versatile while keeping operators safely at atmospheric pressure in a cozy control room.

A good illustration of the complexity of deep-sea tourism is the world-famous Titanic wreck. Despite the rough location of where the ship had sunk having been known within moments of the ship’s demise and broadcast around the world, it would nevertheless take many decades before a mission could be funded and navigate around in the pitch dark before stumbling over the wreck. Even then, Robert Ballard’s mission to Titanic came at the tail-end of a US Navy funded mission to map the wreck of the USS Scorpion.

Since that time, tourism trips to the wreck have become commonplace, offering people with well-filled pockets a chance to see the wreck with their own eyes, as well as land on the wreck’s deck, steal artefacts and litter. With the wreck being in international waters, these dives are essentially unregulated, and legal battles about ownership of the wreck remain, even as the tourist trips have accelerated the decay of the wreck. Perhaps ironically, a recent tourist trip to the wreck in a submersible called the Titan, owned by a company called OceanGate, resulted in the carbon fiber pressure hull failing.

The subsequent implosion shredded the submersible and instantly killed its five occupants, making it the first lethal submersible accident in many years. In addition to adding a second famous debris field alongside that of the Titanic, this event served to underline that for all the progress we have made since the 1940s the oceanic depths is not a place where you want to take shortcuts when it comes to safety.

The pertinent question here would seem to be one of necessity. For industrial purposes, ROVs have proven themselves to be the clear choice for underwater operations, and presumably ROVs would also be used for the mining of manganese nodules in shallower and deep waters. Doing so enables an increase in operating efficiency, while removing significant risk to the ROV operators.

This contrasts with tourism, which is an industry that is very much focused on getting squishy human bodies to a specific physical location where they can use their Mark I eyeballs to gawk at whatever is worthy of attention, whether it’s a beach in Brazil, the peak of some blizzard-blasted mountain, or the lightless depths where 1,500 souls found their demise.

0 Commentaires