Your airplane has crashed at sea. You are perched in a lifeboat and you need to call for help. Today you might reach for a satellite phone, but in World War II you would more likely turn a crank on a special survival radio.

These radios originated in Germany but were soon copied by the British and the United States. In addition to just being a bit of history, we can learn a few lessons from these radios. The designers clearly thought about the challenges stranded personnel would face and came up with novel solutions. For example, how do you loft a 300-foot wire up to use as an antenna? Would you believe a kite or even a balloon?

Why Such a Big Antenna?

The international rescue frequency in those days was 500 kHz. This allowed simple spark gap transmitters to be placed on lifeboats even in the 1920s. Unfortunately that is 600 meters wavelength! A quarter-wave antenna at that frequency is 150 meters long or nearly 500 feet.

After the Titanic sunk, ships maintained a watch on 500 kHz, and ground-wave propagation ensured a good range. Even after spark gaps fell out of favor, they continued to be allowed on lifeboats due to their simplicity. So by the time the war started, 500 kHz was the frequency everyone monitored for distress traffic

History

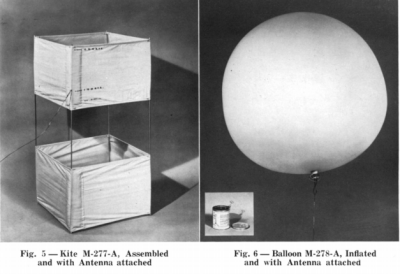

The German NS2 (or NSG2) was a two-tube 500 kHz transmitter with a crystal oscillator. In 1941, the British captured one and created their own version, the T-1333. A second captured unit went to the United States, spawning the SCR-578 and its transmitter, the BC-778. An SCR-578 had a folded metal frame for making a box kite and a balloon with a hydrogen generator. Water would cause the generator to produce gas and the balloon would carry one end of the antenna aloft. The 4.8W transmitter could reach about 200 miles with its 300 feet of antenna wire lofted into the air. You needed at least 175 feet of antenna out for the radio to work.

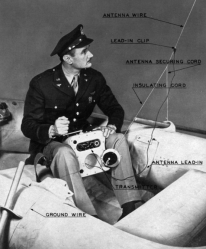

The designers knew you wouldn’t be able to erect that much wire in a life raft. The kite or balloon were workable solutions and would deploy the antenna from a reel mounted in the radio (you can watch a modern-day kite launch in the video, below). Not only that, they could obviously envision what the situation would be like on a tiny raft bobbing around. These radios all had a shape designed to clamp between your knees during operation. The hourglass-like shape spawned the nickname “Gibson Girl” after the illustrations of Charles Dana Gibson. They were also waterproof and made to float.

There were variations. The NSG2 produced 8 watts out using a crystal oscillator while the United States version didn’t use a crystal — they were in short supply — and produced less power. The T1333 used a flare gun to launch the kite folded up, which would deploy at 200 feet. It was also rectangular and had pads to allow the operator to grip the box in operation and didn’t have a balloon.

The entire kit weighed about 33 pounds and included a signal lamp, two balloons, two water-activated hydrogen generators, two rolls of antenna wire, and a parachute so you could drop the whole bag from an airplane.

A True Lifeline

It would be a pretty bad situation if you fished out your survival radio when you needed it and found the batteries were dead. That’s why these radios typically had cranks to generate electricity. No batteries to replace or wear out. If you had enough strength to turn the crank, you were on the air. The crank could also automatically send SOS.

If you want to read more about these old radios, check out [RadioNerd’s] scans of the military manuals. There’s a lot of detail there. For example, it explains that the hydrogen generator uses lithium hydride to produce hydrogen gas when exposed to water. The automated system for sending SOS, AA, or dashes was clever and something we’d do with a microcontroller today but in the 1940s, required mechanical engineering. The circuit description is interesting, too.

The design was durable. Both military and civilian aircraft used the SCR-578 or its direct descendant the AN/CRT-3 until the 1970s. The newer radio acted like the older one, but could also transmit on 8,364 kHz. The Russians started making copies of the original transmitter in 1945. The AVRA-45 is hard to tell from its American counterpart, apart from the lettering on the case.

Hindsight

I don’t know which German engineers at Frieseke & Höpfner GmBH designed the NS2, but they were clearly thinking about their users and willing to solve problems in the true hacker fashion. The shape is easy to grip, the crank does away with battery problems, and the radio is suited for its intended use. You have to wonder what other ideas they had for lifting the antenna before they settled for the balloon and kite combo. I also wonder why the British kite is so different and requires a Very pistol to launch.

Of course, this wasn’t the first example of a kite-lofted antenna. In 1898, a weather balloon lifted an antenna over Massachusetts and in 1901, Marconi’s antenna at Newfoundland would communicate with England while connected to a man-carrying observation kite. Military use dates back to at least 1905 with the United States Army using them as late as 1920. The British and Germans were using them around the turn of the century, too and the U.S. Navy had kite-based antennas on seaplanes in 1922. Still, the NS2 was a marvel of packaging and practicality.

The NS2 was the successor to the heavier NS1. While it did have a kite, it also had an ungainly aluminum antenna for use with no wind and it also relied on batteries. You can presume that by taking honest feedback on the NS1, the engineers were able to build the NS2 and they really hit the mark. After all, isn’t imitation the sincerest form of flattery? I doubt those engineers considered themselves hackers — that term wasn’t even in use then — but I do.

It is amazing how simple a radio can be if you are motivated enough. Don’t think hams haven’t used balloons before, either.

[Main image source: German WWII emergency kite by Helge Fykse]

0 Commentaires