After decades in development, the Philippines became the first country on July 21st of this year to formally approve the commercial propagation of so-called golden rice. This is a rice strain that has been genetically engineered to produce beta-carotene in its grains. This is the same compound that has made carrots so famous, and is a significant source of vitamin A.

Getting enough vitamin A is essential for not only children and newborns, but also for pregnant and lactating women. Currently, vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is the primary cause of preventable childhood blindness and an important cause of infant mortality. While VAD is hardly the only major form of world-wide malnutrition, biofortification efforts like golden rice stand to dramatically improve the lives of millions of people around the globe by reducing the impact of VAD.

This raises questions of how effective initiatives like golden rice are likely to be, and whether biofortification of staple foods may become more common in the future, including in the US where fortification of foods has already become commonplace.

Making Plants Do Our Bidding

The domestication of plants is an ongoing process, started by humankind thousands of years ago when early farmers began to select for and cultivate specific plants with desirable traits. Over many generations of plants, this would gradually produce many domesticated crops with which we are familiar today. This artificial selection process increased the size of fruits and grains, made crops easier to process and consume, and increased yield.

The 20th century saw the rise of intensive agriculture, leading to the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ between the 1940s and 1970s during which world-wide agriculture saw major boosts in yields through technology: artificial fertilizer, improved irrigation, and improved harvesting methods, but also a more concentrated artificial selection of plants.

Through mutation breeding – also known as mutagenic, or variation breeding, as well as mutagenesis – plant seeds are exposed to mutagenic sources of chemicals, radiation or enzymes to create genetic mutants. This introduces random changes to the genome of the plant’s cells, which may result in desirable changes on which can be selected.

Or not. Effectively this isn’t very different from what happens naturally, except much faster and at a much greater pace, and with unfortunately the same problem of undesirable mutations creeping up as well, which may cripple or kill an affected plant. Although this makes it a slow and laborious process, mutagenics is responsible for thousands of fruit and vegetable types we buy in the supermarket today.

Genetic modification can be contrasted with genetic engineering (GE), where the plant’s genome is directly edited in order to effect the desired alterations. The benefits of genetic engineering are obvious: changes are appear instantly, and undesired mutations are avoided.

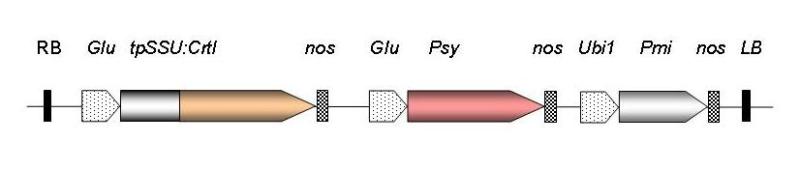

In addition, in GE plants, genetic abilities can be introduced that are otherwise foreign to the plant, such as producing beta-carotene in its grains. Even with mutagenic GM plants, such a major change is unlikely to ever occur spontaneously. In the current version of golden rice (GR2), the CrtI gene from Pantoea ananatis and the phytoene synthase gene (Psy) from Zea mays (maize) are added to complete the beta-carotene pathway which is incomplete for the rice grain.

Making The Case For Beta-Carotene In Rice Grains

Carotenes are generally considered to be an essential component in the ability of plants to photosynthesize. This explains why beta-carotene is a common component in leafy greens, such as kale, spinach and broccoli, as well as pumpkins and carrots. Unfortunately, none of these leafy greens, nor animal sources of vitamin A, are readily available in many parts of the world, or affordable if they are.

As noted by Saeed Akhtar et al., there are three ways to fix VAD: supplementation, fortification, and dietary diversification. Vitamin A supplementation is only somewhat effective because it relies on a government organization providing everyone in need with regular supplementation. Supplementation with vitamin A also becomes less efficient when one’s body has less fat because it is fat-soluble. Similarly, fortification requires that someone adds vitamin A (or beta-carotene) to the food stuffs, which presumes that government regulations on food fortification aren’t dodged, as Akhtar et al. found to be common in some areas.

Akhtar et al. came to the conclusion that a diversified, multi-prong approach is most likely to be effective here, as weakness in one approach can cover weaknesses in another approach.

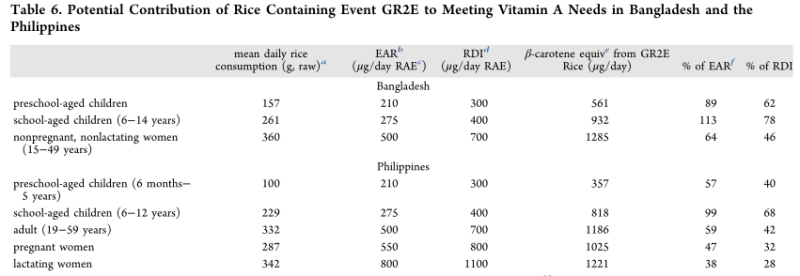

As golden rice does not require anything beyond the usual planting and harvesting of rice, it adds no extra burden, but merely raises the question of how effective it is. That is, how much vitamin A does a person who consumes a certain amount of golden rice convert from the beta-carotene in the rice grains?

A 2019 study by Swamy et al. found that in an analysis of golden rice versus regular rice as grown in the Philippines during 2015-2016, the only noticeable difference was the presence of beta-carotene and other provitamin A carotenoids. Based on the levels of beta-carotene present, they calculated that 100 grams of raw golden rice could provide 30-40% of the recommended daily intake (RDI) of vitamin A for children, and 11-13% for adult women. It’s not a complete solution by any means, but it helps.

Nobody Is Perfect

Perhaps the most ironic thing about malnutrition is that merely living in a country where one has ready access to (fortified) food and supplements does not guarantee that one cannot suffer from especially micronutrient deficiencies. Scurvy due to lack of vitamin C has been making a resurgence in the US (Al-Dabagh, et al.), as well as France (Chalouhi et al.), and in Australia. Overcooking food and eating heavily processed fast food are common factors here.

This touches upon the psychological causes behind malnutrition, where people willingly refuse to eat a diet that contains the nutrients they need to consume in order to stay healthy. Who doesn’t know the image of the child who doesn’t want to eat their veggies, only to be told by their parents about the poor children in developing nations who would jump at the chance to eat their meal instead?

However, when in developing nations the main problem is the lack of a diverse diet that provides all of the required nutrients for a healthy development, how does one go about addressing malnutrition in developed countries? The struggle against malnutrition does appear to have many faces, for which a multitude of solutions would be required.

It should be noted here first and foremost that there is no evidence of a drop in the nutritional value of vegetables, beyond an increase in carbohydrates which can be attributed to the dilution effect caused by the increased yield. This is detailed by Robin J. Marles in a 2016 literature review article. Essentially, if one were to eat their vegetables and fruit, along with protein sources, no nutritional deficiency should exist in developed nations.

Easy And Hard Questions

When it comes to solving malnutrition in developing nations, it seems clear that biofortification efforts like golden rice can help reduce the health issues that come from lack of micronutrients. The effort required is also relatively low. With Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and now the US having declared golden rice safe for consumption, it seems that at least this biofortified food source may herald the beginning of the end of malnutrition in developing countries.

Even so, unhealthy diets are a global issue, according to the 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GDB) study, despite many of the people affected having ready access to the ingredients for such a healthy diet. A major issue in developed nations was for example the significant intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, along with the elevated intake of processed meat, sodium, and red meat.

It’s perhaps ironic that solving particular sources of malnutrition in developing nations is as straightforward as changing to a crop like golden rice or other biofortifed foods, while in richer countries the problem is behavioral and much less obviously solved.

0 Commentaires