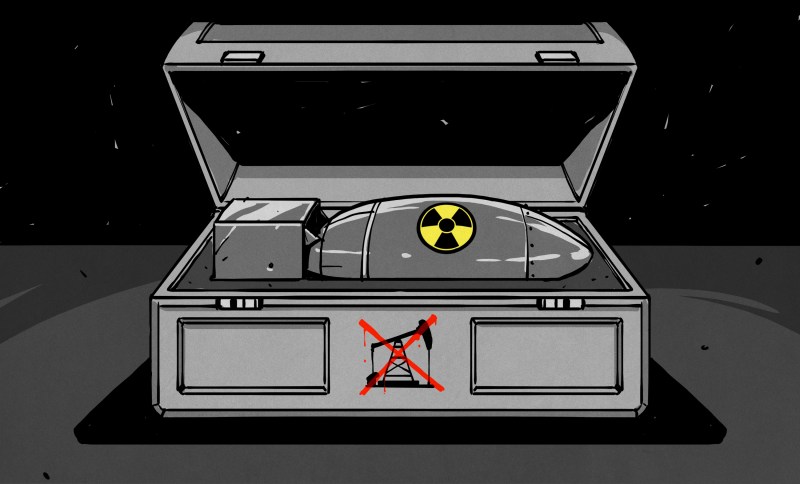

Nuclear explosives were first developed as weapons of war in the pitched environment of World War II. However, after the war had passed, thoughts turned to alternative uses for this new powerful technology. Scientists and engineers alike dreamed up wild schemes to dig new canals or blast humans into space with the mighty power of the atom.

Few of these ever came to pass, with radiological concerns being the most common reason why. However, the Soviet Union did in fact manage to put nuclear explosions to good use for civilian ends. One of the first examples was using a nuke to plug an out-of-control gas well in the mid 1960s.

The Conventional Method Attempted

On December 1, 1963, Well No. 11 in the Urta-Bulak gas field suffered a blowout due to a violation of proper drilling procedures. The 2409 meter deep hole opened up a gas reservoir underground with pressure of 300 atm. The blowout caused significant destruction in its wake, and the gas quickly caught fire at the surface, stretching 120 meters into the sky. Tractors were used to clear the site, but the flame continued burning 12 million cubic meters of gas every day.

The situation was a difficult one from the outset. Initial attempts used water to cool the area and reduce the size of the flame so that diverters could be installed to redirect the gas and burn it off safely.

Well No. 11 wasn’t giving up without a fight however, and the pressure restriction introduced by the new diverter cap simply led to the gas permeating other subsurface layers around the original borehole. The gas had a high hydrogen sulfide content, and craters began forming at the surface with the poisonous gas bubbling up from underground. This situation was far too dangerous to continue, so the diverter was removed shortly after.

Two more years were spent trying to stem the flow of gas with traditional methods. Multiple relief wells were drilled in an attempt to pump fluid into the gas formation to stem the flow. However, the problem was that the original Well no. 11 had been drilled well off-vertical, being up to 120 meters off-target at the 2400-2600m depth. Thus, drilling a relief bore was difficult as crews didn’t know exactly where they really should be drilling to gain access to the reservoir.

Screw It, Time For Nukes

The summer of 1966 saw a new plan come to fruition, spawning a film which followed the experiment along the way. The Soviet government had recently established a program to explore the use of nuclear explosions for peaceful ends, by the name of Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy. The aim was to explore a wide variety of ways in which powerful nuclear explosives could help achieve peaceful goals in industry and other fields.

With the new program up and running, the leaders were approached as to whether a nuclear explosion might be put to the task of closing the recalcitrant Well No. 11 at the Urta-Bulak gas fields. The hope was that a nuclear explosion underground, next to the well, could squeeze the hole closed. The plan called for a 30 kiloton nuclear device to be detonated within approximately 25-50 meters of the original well hole. Geological analysis suggested that the well should be pinched off approximately 1500 meters underground. This depth featured sandstone sediments beneath a thick layer of clay above, with the clay considered likely to be non-permeable enough to seal off the well.

To achieve the task, the well’s actual path had to be determined, and it was eventually found to be 50-60 meters to the northeast of its intended vertical path at the 1500 meter depth. With the location of the well now known, a killing well was carefully drilled that would allow the nuclear device to be placed in an appropriately close position.

Huge amounts of equipment were brought on site to handle the task. Radiological and seismic monitors were all on hand for the first-of-its-kind experiment. A command station was established on site to allow the nuclear device to be detonated, specially built for the purpose by the Arzamas nuclear weapons laboratory. The nuclear explosive was carefully lowered into place, and the killing well was then cemented in order to avoid leaving a secondary path for gas to leak to other geological strata underground.

The device was detonated on the morning of September 30, 1966, by which point the well had been leaking gas for a full 2 years and 9 months. A 5 km blast radius was cleared for safety, with all personnel and vehicles removed from this area. The explosion was surprisingly undramatic, with a slight shift seen in the ground and a rumble heard and felt, but little more than that. The gas flare immmediately began to shrink, and extinguished just 23 seconds after detonation.

Radiological safety planes flew over ground zero shortly after, reporting no major radiation above background and no traces of methane. Radiation at ground level was also detected to be within usual limits. Overall, the experiment had worked, quickly bringing to an end what had been a thus far intractable problem. From there, it was a simple job of sealing up the upper section of the well and putting to rest what had been a long and difficult chapter in the Urta-Bulak gas fields.

Four More Times

Sealing off the well saved billions of cubic meters of gas from being wasted, and the experiment was seen as a great success. As explored in a wide-ranging US government report from 1996, the Soviets went on to use the same concept a total of four more times. Wells at the Pamuk, Mayskii, and Krestishche gas fields were each successfully sealed off with nuclear devices from 1968 to 1972. The last attempt was made in 1981, at a well in the Kumzhinsky gas deposit on Russia’s northern coast. Details are scarce, but the explosion failed to seal the well, potentially due to poor information on the location of the target to be sealed.

Since then, the concept of using nuclear explosions for peaceful ends has largely fallen out of favor. Concerns about radiological contamination, nuclear proliferation, and the potential theft and misdirection of nuclear devices have all been cited as reasons against such use. The Soviet program itself ended after moratoriums on nuclear testing came in to being in the late 80s and early 90s. However, as the Soviets demonstrated ably in the mid-20th century, a nuclear explosion could seal a blown out gas well. On those merits and those merits alone, it did the job!

0 Commentaires