When we last left the post office, I told you all about various kinds of machinery the USPS uses to move mail around. Today I’m going to tell you about the time they thought they could automate nearly every function inside the standard post office — and no, it wasn’t anytime recently.

By 1953, the post office badly needed modernization. When Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield was appointed that year, he found the system essentially in shambles. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, the USPS had done absolutely no spending beyond the necessary, with little to no investment in the future. But Summerfield was an ideas man, and he had the notion to build a totally automated post office. One of them would be located in Providence, Rhode Island and be known as Project Turnkey — as in a turnkey operation. The other would be located in Oakland, California, and serve as a gateway to the Pacific.

The Post Office of Tomorrow

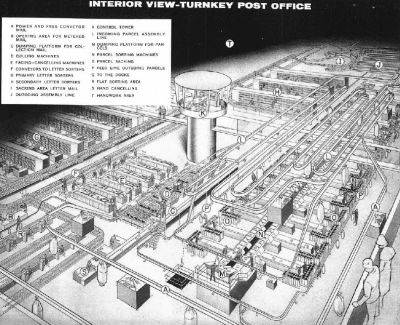

Turnkey opened on October 20, 1960, and was quite a building. It was a one-story affair, 420′ long, 300′ wide, and 55′ high, but only had two supporting columns in order to maximize floor and equipment space.

Both a distribution center and a regular post office, the building was nestled amid several major transportation routes. Ideally, Project Turnkey would show the world its worth by first speeding mail around Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts.

The point of such an automated post office was to be a proving ground for new machinery, a laboratory for postal invention. Just as we learned last time, processing begins with cullers that separate out the packages from letters and flats. The cullers take similarly-sized letters and stack them neatly in trays, although they are going every which way. Then it’s on to the facer-canceller, which locates the postage and faces the mail piece for cancellation.

So, Not Exactly Automated

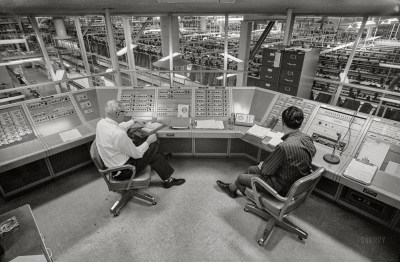

Although a automated post office, Turnkey was not without human intervention. After coming out of the facer-canceller, trays of letters would travel to semi-automated sorting compounds where employees hand-coded in destinations. Then the letters would be sacked up.

Packages moved much the same way — faced by machines, taken by conveyors to humans to hand-code the destinations, and whisked away in canvas sacks.

The numbers that came out of Turnkey were fairly impressive. The sorters were capable of routing letters to 30 destinations. The cullers and the facer-cancellers were cranking out 25,000 pieces per hour.

But far from being a fully-automated post office, Turnkey required 1,500 employees to run the thing, which was about 100 more than the previous post office.

Project Turkey

In hindsight, Project Turnkey seemed doomed from the start. Its origins were political in nature, and the building was dedicated just weeks before the Kennedy vs. Nixon election. Afterward, little attention was paid to the project, which had cost around $20 million to build.

More importantly, the employees were inadequately trained on the machinery, some of which ended up being under-utilized or not used at all.

Unfortunately, Turkey didn’t have any of its problems locked up. Some enterprising scalawag sent a letter through Turnkey with a Russian stamp on it (in 1960!), and — you know it — the thing was culled, faced, cancelled, and delivered. And because humanity can behave speaking collectively like it’s twelve years old, this inspired copycat stunts. See, and then they just had to add more humans.

By March of 1961, Projects Turnkey and Gateway were declared a failure, first by the Washington Post. Critics referred to it as “Project Turkey.” Apparently the House Postal Appropriations Subcommittee told the USPS to stop paying Intelex, from whom they were leasing the expensive Turnkey building. Additionally, the newly-elected Postmaster General J. Edward Day was much more grounded when it came to the day-to-day operations of the USPS.

But Wait, There’s More

Of course, that wasn’t the end of postal automation. Stay tuned for more about the USPS’ advancements, including OCR machines, ZIP codes, vending machines, and something called v-mail. We’ll also take a look at ways the USPS has attempted to improve productivity and service as well as the customer experience. And no, I haven’t forgotten about that bit of trivia.

0 Commentaires